This is a guest post by Sean Fox at the LSE

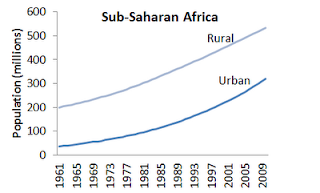

Popular accounts of life in African cities typically portray

a Dickensian squalor in the tropics: unkempt masses struggling with

poverty, disease and violence. While such accounts overlook the dynamic

nature of African cities and the resilience of their residents, they

do reflect an important truth. Sub-Saharan

Africa has the highest rate of ‘slum incidence’ of any major world region, with

over 60% of the region’s urban population—roughly 200 million people—living in

settlements characterized by some combination of overcrowding, tenuous dwelling

structures, and deficient access to adequate water and sanitation facilities. However,

there is wide variation in slum incidence across countries within the region (see

Table 1). Why do so many Africans live in slums, and what accounts for the wide

variation in slum incidence across countries in the region? I address these

questions in a

recently

published working paper.

Table 1 - Slum

incidence by region and for selected African countries

|

Slum population

as % of urban population

|

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

Region

|

|

|

|

Developing Regions

|

39.3

|

35.7

|

32.7

|

Sub-Saharan Africa

|

65.0

|

63.0

|

61.7

|

Southern Asia

|

45.8

|

40.0

|

35.0

|

South-eastern Asia

|

39.6

|

34.2

|

31.0

|

Eastern Asia

|

37.4

|

33.0

|

28.2

|

Western Asia

|

20.6

|

25.8

|

24.6

|

Latin America & the Caribbean

|

29.2

|

25.5

|

23.5

|

Northern Africa

|

20.3

|

13.4

|

13.3

|

Selected

African countries

|

|

|

|

Ethiopia

|

88.6

|

81.8

|

|

Tanzania

|

70.1

|

66.4

|

|

Nigeria

|

69.6

|

65.8

|

|

Ghana

|

52.1

|

45.4

|

|

South Africa

|

33.2

|

28.7

|

|

Zimbabwe

|

3.3

|

17.9

|

|

Source: UN-Habitat (2008)

|

Social scientists have traditionally portrayed slums as a

natural and temporary by-product of economic modernization. But the scale and

persistence of slum settlements in developing regions in recent decades

presents a serious challenge to this notion. A variety of theories have been

advanced to account for this apparent deviation from the assumed path of

modernization. Put together they tell a fairly simple story: urban population

growth in developing regions has outpaced economic and institutional

modernization. I refer to this as the ‘disjointed modernization’ theory of

slums and test it empirically using regression analysis. In support of this

theory, I find that nearly 70% of cross-country variation in slum incidence can

be accounted for by variation in urban population growth rates, measures of

income and economic diversification and a measure of institutional quality.

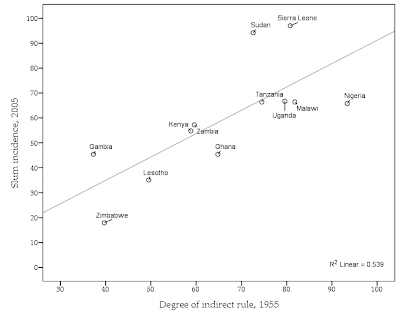

However, identifying the contemporary correlates of slum

incidence does not amount to a convincing causal explanation for the scale and

diversity of the phenomenon. Why did the process of modernization become more

disjointed in some countries than others? To answer this question I trace the

origins of divergence in urban development trajectories back to the colonial

era. Generally speaking, colonisers stimulated urban population growth but laid

a poor foundation for urban economic development and effective urban governance.

But colonial experiences varied widely across countries in Africa. Where

economic and political interests were strong, towns and cities received significant

investment and institutional development; where economic and political

interests were relatively marginal, towns and cities received minimal

investment and were left with ad-hoc governance structures. I demonstrate that

this variation is correlated with contemporary slum incidence. For example,

Figure 1 below plots slum incidence against a measure of ‘British indirect

rule’—i.e. the number of court cases adjudicated by indigenous as opposed to

colonial authorities. The figure shows that slum incidence in 2005 is closely

correlated with the measure of British indirect rule (a proxy for institutional

investment) in 1955, supporting the hypothesis that the colonial era represents

a ‘critical juncture’ in the history of urban development in sub-Saharan

Africa.

Figure 1. Colonial strategies of rule and slum incidence in 2005

Having identified the colonial origins of ‘disjointed’

modernization, I turn my attention to the mechanisms of path dependency that

have served to perpetuate colonial patterns of urban investment and

institutional development. Post-colonial African governments have had anywhere between

25 and 50 years to redress the failures of their colonial forebears. Why have

they not done so? I offer two complementary explanations.

First, urban underdevelopment offers myriad opportunities

for political and economic entrepreneurs. For example, politicians and

bureaucrats often use the absence of formal property rights in urban areas to

engage in ‘land racketeering’—i.e. offering squatters on ‘public’ land

protection from eviction in return for political support or economic rents. Similarly,

the absence of water infrastructure yields very lucrative opportunities for the

private vendors who inevitably step in to fill the void. In other words, urban underdevelopment has proven very

profitable for a range of actors in African cities, resulting in the emergence

of a broad constellation of status quo interests opposed to investment and

institutional reform.

Second, an anti-urbanization bias emerged in development

discourse and practice in the late 1970s. Up to that point, towns and cities

were seen as engines of prosperity and progressive social and political spaces.

But a series of influential publications in the 1970s and 1980s portrayed

urbanites as economic parasites feeding off the surplus produced by peasants in

the countryside and exerting an undue influence in public affairs. Investing

in urban development came to be seen as anti-developmental.

As a result, governments across Africa implemented policies to restrict or

discourage rural-urban migration and promote rural development. By 2007, 78% of

African countries had policies in place to restrict migration; up from 49% in

1976. There was also a significant contraction in international development

assistance for urban development projects. As Table 2 demonstrates, World Bank

shelter lending in the region, which began in 1972, shrivelled to near

insignificance by 2005.

Table 2. Trends in World Bank shelter lending in sub-Saharan Africa,

1971-2005

|

1972-1981

|

1982-1991

|

1992-2005

|

Total

shelter lending

|

$498 million

|

$409 million

|

$81 million

|

Equivalent

per capita

|

$5.20

|

$2.74

|

$0.32

|

Notes: Shelter lending data from Buckley and Kalarickal (2006); per capita

estimates based on total urban population in sub-Saharan Africa at the end of

each period (i.e. 1981, 1991 and 2005) drawn from World Bank, World

Development Indicators online database, accessed September 2012.

|

The proliferation of slums in sub-Saharan Africa in recent

decades is de facto evidence of government failure to invest in urban

development. But history is not destiny. As Africa’s urban population continues

to grow, politicians are increasingly likely to find it in their inteest to

address the basic needs of urban residents. And if they are committed to

stimulating economic growth and diversification they will need to do so. Cities

can serve as engines of economic development, but only if they have adequate

infrastructure and their residents have safe, healthy and secure places to

live. The international community could help facilitate this transformation by

recognizing the urban potential and supporting (as opposed to discouraging)

efforts to invest in urban development in the region.

-----

Fox, S. (2013) ‘The political economy of slums: Theory and

evidence from sub-Saharan Africa’,

Working paper series 2013, No. 13-146, Department of International Development,

London School of Economics and Political Science.