"Well, one thing that did certainly affect it is the tactics of how to reform, in the sense that, certainly in academia, you are basically told you need to think deeply. Then there are a lot of pressure groups, lobbies, so you need to talk to them. You need to use the media for communicating the benefits of reform, and so on. Some of the reformers, successful reformers that I spoke with, before I joined the Bulgarian government, basically I said, 'You go, and on Day 1, you surprise everybody. So, you go in every direction you can, because they will be confused what's happening and you may actually be successful in some of the reforms. So, this is what I did. I went to Bulgaria in late July 2009; the Eurozone Crisis had already started around us. Greece was just about to collapse a few months later. So, there was kind of a feeling that something is to happen. But, instead of going, 'Let's now do labor reform,' then, 'Let's do business entry reform,' in the government we literally went 6 or 7 different directions hoping that Parliament will be, you know, confused or too happy to be elected--they were just elected. And we actually succeeded in most of these reforms. When I tried to do meaningful, well-explained reforms two years after, they all got bogged down, because lobbying will essentially take over and, 'Not now; let's wait for next year's government,' and so on."From the always interesting Econ Talk.

30 November 2024

How to achieve public policy reform by surprise and confusion

03 April 2025

The Political Economy of Underinvestment in Education

21 January 2025

The Political Economy of Education in Uganda

This post was first published on the CGD Views from the Center Blog

Uganda goes to the polls in 30 days to elect its next president, but there is little sign so far in the public debate on education of the need to shift focus from inputs and enrolment to actual learning outcomes.

I was in Kampala last week piloting a survey on school management (more on that later), and spotted in the Daily Monitor a feature on the candidate’s campaign promises on education, reading as follows:

Yoweri Museveni

- One primary school per parish (to reduce average walking distances)

- Continue to increase the budget allocation for text books

Kizza Besigye

- Introduce compulsory universal primary education

- Increase remuneration for primary school teachers

Amama Mbabazi

- Recruit and train new teachers with the aim of reducing the teacher-student ratio

- Build more schools and classrooms

That’s zero mention of actual student learning outcomes from any of the leading candidates, and a complete focus on spending more money and providing more of the inputs that have been showntime and again to bear little relationship with improved learning outcomes.

NYU Professor David Stasavage published a paper in 2005 exploring how the introduction of elections in Uganda in 1996 helped lead to the removal of school fees in 1997. He also published a follow-up in 2013 noting how elections focus politicians on those things that are easily visible to voters. Fees for tuition at public schools are very visible to voters, and so one of the first things democratic politicians address. School quality is much less visible to the average voter, leading to much less focus on teaching and learning by politicians.

All of this suggests that one way to improve student learning is to get citizens and politicians more focused on learning by better measurement and spreading of the insight that despite high enrolment, student skills are very poor. This is a key part of the theory of change behind the global ASER/Uwezo/PAL-Network movement of citizen-led student reading assessments. What sadly seems clear from Uganda is that this message has not yet got through. We’ve known since Uwezo’s 2010 assessment that children in Uganda are way behind where there should be (only 2 percent of grade 3 children could read and understand a grade 2 story).

My tip for anyone with the opportunity to grill the candidates on education policy would be to borrow Paul Atherton’s mantra: “But can the kids read?”

03 June 2025

Why governments don't like private schools?

1. The first page of each [book] starts with the words “Hugo Chavez: Supreme Commander of the Bolivarian Revolution.”

2. They describe Chavez as the man who liberated Venezuela from tyranny, at times making him appear more important than 19th century founding father Simon Bolivar.

3. The books present a 2002 coup that briefly toppled Chavez as an insurrection planned by Washington while playing down the role of massive opposition protests in this deeply divided country.

27 January 2025

Safety nets and economic growth

To those possible avenues, Harold Alderman and Ruslan Yemtsov (ungated) now add:

- improving financial markets

- improving insurance markets

- improving infrastructure (through public works programmes), and

- relaxing political barriers to policy change

But this political point goes beyond relaxing barriers to policy change, to relaxing barriers to technological change. Otis Reid pointed out to me this paper by economic historians Avner Greif and Murat Iyigun which argues that:

"England’s premodern social institutions-specifically, the Old Poor Law (1601-1834)-contributed to her transition to the modern economy. It reduced violent, innovation-inhibiting reactions from the economic agents threatened by economic change."To be crude - it's worth paying off the Luddites so they don't get in the way of growth-enhancing technological change.

02 May 2025

The political economy of Nigeria and Indonesia

A Nigerian and an Indonesian attend a foreign university together in the 1960s and become friends. After graduation, each returns home to join the government. Several years later, the Nigerian visits his colleague in Jakarta, and finds him living in a big, luxurious house with a Mercedes car parked outside. ‘How can you afford such a nice house on a politician's salary?', asks the Nigerian. ‘Do you see that road?', replies the Indonesian, pointing to a magnificent highway outside. ‘Ten per cent.' Some time later, the Indonesian goes to visit his Nigerian friend, and finds him living in a vast palace with ten Mercedes cars parked outside. Amazed, he asks where the money had come from. ‘Do you see that road?' asks the Nigerian, pointing to a thick tangle of rain forest. ‘A hundred per cent.'From the Economist (old, but good)

15 November 2024

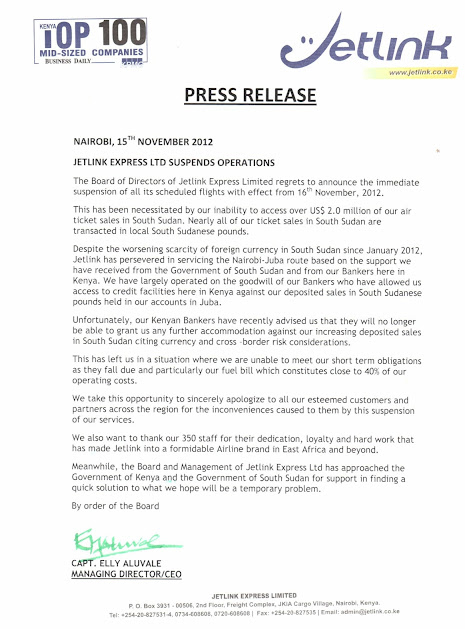

The cost of currency controls in South Sudan

HT: @bankelele

14 May 2025

Millennium Villages: impact evaluation is almost besides the point

"What is the impact of the Millennium Village package of interventions on the area in question?"

The really depressing part though is that this is actually the least interesting question. Chances are that throwing in a whole bunch of extra inputs to a community will create some outputs, and some impact. The whole point of the Millennium Villages though is to provide a model for the rest of rural Africa to follow. The really interesting question is whether African governments have the desire and capability to manage a massive and complex scaling up of integrated service delivery across rural Africa.

A point which basically belongs to Bill Easterly.

Mr. Easterly argues that the Millennium approach would not work on a bigger scale because if expanded, “it immediately runs into the problems we’ve all been talking about: corruption, bad leadership, ethnic politics.”

He said, “Sachs is essentially trying to create an island of success in a sea of failure, and maybe he’s done that, but it doesn’t address the sea of failure.”

Mr. Easterly and others have criticized Mr. Sachs as not paying enough attention to bigger-picture issues like governance and corruption, which have stymied some of the best-intentioned and best-financed aid projects.

Another challenge in some sites is insufficient capacity of local government to take full ownership of MV activities. This is manifested in unfulfilled pledges to perform mandated roles, unsatisfactory maintenance of infrastructure, and insufficient involvement of local elected officials. MV site teams are addressing these challenges by agreeing to jointly implement interventions targeted at improving the performance of sub‐district governments, increasing sensitization and engagement of local government officials, increasing joint monitoring of MV activities in communities, and developing training plans in technical, managerial, and planning skills for local government officials.Or : "we have no clue how to fix the systemic implementation challenges"

An anonymous aidworker writes on his blog Bottom-up thinking

I’ve noticed around here, normally sloth-like civil servants who won’t even sit in a meeting without a generous per diem rush around like lauded socialist workers striving manly (or womanly) in the name of their country when a bigwig is due to visit, working into the night and through weekends, all without any per diems...

I fear all the achievements of the MVP will wash up against the great brick wall that is a change resistant bureaucracy.None of this is to say that the situation is hopeless. It isn't. In particular there are elements of the Millennium Village package which are proven to be effective, cheap, and don't require complicated systems of governance and accountability. Namely distributing insecticide-treated bednets. Aid money can provide them easily, sustainability is less of a concern than other interventions, and you can buy them right now. Check out Givewell for a rigorous independent assessment (and recommendation) of the Against Malaria Foundation. Probably the single best way you could spend some money today.

02 May 2025

Black Economic Empowerment

Many black capitalists have been brought on board the corporate bandwagon because of their political connections, not for their Weberian entrepreneurial ethic, so many BEE deals collapse into cronyism and corruption, who-you-know mattering more than what-you-know.

Meanwhile, corporate cynicism knows few bounds. Unbundled fragments are transferred to indebted black satraps, and black capitalist success hovers uneasily between dependence on state contracts and white corporate goodwill. Increasingly, too, large corporates are shifting major interests into private equity.

BEE remains a necessary political project. Leaving white capital to transform itself is like asking the devil to convert to Catholicism. But the challenges are immense: can a well-intentioned but under-capacitated state shape a socially responsible capitalism, or is BEE creating an avaricious class of black capitalists tied to the coattails of international capital?

23 April 2025

Uttar Pradesh Fact of the Day

“...teachers constitute 20 percent of the assembly in the early 2000s, and former teachers another 20 percent.”

From this: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1895224For a bit of perspective on why that matters, consider that

With a population of over 200 million people, [Uttar Pradesh] is India's most populous state, as well as the world's most populous sub-national entity. Were it a nation in its own right, Uttar Pradesh would be the world's fifth most populous country, ahead of Braziland then consider that

“the most striking weakness of the schooling system in rural Uttar Pradesh is not so much the deficiency of physical infrastructure as the poor functioning of the existing facilities. The specific problem of endemic teacher absenteeism and shirking, which emerged again and again in the course of our investigation, plays a central part in that failure. This is by far the most important issue of education policy in Uttar Pradesh today”(that last part is Dreze & Gazdar, quoted by Kingdon and Muzammil in "A political economy of education in India: The case of Uttar Pradesh", HT:Abhi).

This post is dedicated to @DavidTaylor85 and @OfficeGSBrown

17 February 2025

The evolving art of political economy analysis

Over the last 15 years, development actors have increasingly recognised the political and messy nature of reform. Prescribing best practice solutions has often failed given the differing perspectives, capacity and motivations of stakeholders on each side of the aid relationship. Political economy analysis (PEA) has emerged in response to help practitioners close this gap and understand the reform environment in which they are acting. This has led to more realism in the aid industry with more open discussions of power, political culture, ethnic divisions, corruption, sources of opposition and indifference, and so on.

However, PEA as it stands risks becoming another routine element in aid programming, rather than a transforming, innovative influence on how development practice works. For example, the common tool guiding aid programmes - the logical framework - is no doubt enhanced by the use of PEA, for example by ensuring resources are more aligned to local structures, but the fundamental premise of how we act stays the same: goals are set, a logical sequence of actions predicted and all things messy or unknown are relegated to a heading under ‘risks’.

This Development Futures paper charts a new course for PEA to have a more radical impact on development practice. It argues that if we are serious about embracing the political and complex nature of development then we need different ways of acting to confront such complexity. This includes acknowledging our own limited knowledge (an action rarely applauded), the need to collaborate with others to build new knowledge and increased flexibility to react to such analysis as well as other unexpected events. PEA therefore should strive to be more than a technocratic means to understand the commitment and capacity of others but an opportunity for internal learning and adjustment.

To this end, the paper sets out a framework for combining PEAs focus on the macro-politics of recipient country interests with the micro-politics of stakeholder relations, including more self-reflection on the part of donors and consultants. This paves the way for thinking of development practice as iterative cycles of experimentation, discovery, learning and interaction. Whilst this perhaps sounds ambitious, particularly given the current emphasis on visible results and value for money, we argue that these iterative cycles of engagement are already happening. By making them more explicit we can become more effective.

(these views don't necessarily represent the views of OPM or the University of Bath, etc etc.....)

03 January 2025

The Political Economy of Privatisation

Adam Smith or Machiavelli? Political incentives for contracting out local public services

Why do some local governments deliver public services directly while others rely on providers from the private sector? Previous literature on local contracting out and on the privatization of state-owned enterprises have offered two competing interpretations on why center-right governments rely more on private providers. Some maintain that center-right politicians contract out more because, like Adam Smith, they believe in market competition. Others claim that center-right politicians use privatization in a Machiavellian fashion; it is used as a strategy to retain power, by ‘purchasing’ the electoral support of certain constituencies. Using a unique dataset, which includes the political attitudes of over 8,000 Swedish local politicians from 290 municipalities for a period of 10 years, this paper tests these ideological predictions together with additional political economy factors which have been overlooked in previous studies, such as the number of veto players. Results first indicate support for the Machiavellian interpretation, as contracting out increases with electoral competition. Second, irrespective of ideological concerns, municipalities with more veto players in the coalition government contract out fewer services.Yikes!

Policies, Politics, and Poor Economics

Political economy is the view (embraced, as we have seen, by a number of development scholars) that politics has primacy over economics: Institutions define and limit the scope of economic policy.

there is no reason to believe, as the political economy view would have it, that politics always trumps policiesWhich is a bit of a straw man. For example, Benno J. Ndulu and Stephen A. O’Connell write:

Growth depends on the interaction of opportunities with choices.

The central message of the Growth project is to confirm the critical importance of policy for long term growth in SSA.and Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson

Main thesis is that growth is much more likely under inclusive institutions than extractive institutions.

Though growth is much more likely under inclusive institutions, it is still possible under extractive institutions.Their basic point is valid, but maybe just a little oversold. I'm not sure that Acemoglu and Robinson really think that there is nothing at all to be done to improve things in countries with weak institutions.

Finally, they make a point also made by Tony Blair which you don't otherwise tend to hear too much - focusing relentlessly on delivery of something can help to improve governance.

Good policies can also help break the vicious cycle of low expectations: If the government starts to deliver, people will start taking politics more seriously and put pressure on the government to deliver more, rather than opting out or voting unthinkingly for their coethnics or taking up arms against the government.

The political constraints are real, and they make it difficult to find big solutions to big problems. But there is considerable slack to improve institutions and policy at the margin. Careful understanding of the motivations and the constraints of everyone (poor people, civil servants, taxpayers, elected politicians, and so on) can lead to policies and institutions that are better designed, and less likely to be perverted by corruption or dereliction of duty.

Political Economy is Hard

The respected Minister for Civil Service Reform Awut Deng Acuil has resigned for reasons that have not been made clear, and top civil servant Aggrey Tisa Sabuni has been appointed Economic Adviser to the President (from Undersecretary at the Ministry of Finance. Congratulations Tisa!). The implications of these two moves are probably significant, but there just isn't any English-language media analysis.

Doing "political economy analysis" in the UK simply means picking up almost any newspaper on a regular basis. What is a donor supposed to do when they can't do that?

So the implications of this:

(a) if we believe that understanding politics is important for effective policy design, and

(b) we generally aren't very good at understanding politics in developing countries

---> we should probably go for simple interventions with either very high benefit-cost ratios, or with low dependence on understanding local systems.

Sidenote: I did a bit of googling for some analysis of the last Nigerian budget. Well done to PWC for coming up with something. But really, the rest of the whole entire world, we don't think its worth bothering to figure out some way of funding someone to take a really hard serious look at the spending decisions of the government of the most populous country in Africa, and then get surprised when things blow up??