The latest

World Development Report is all about economic geography.

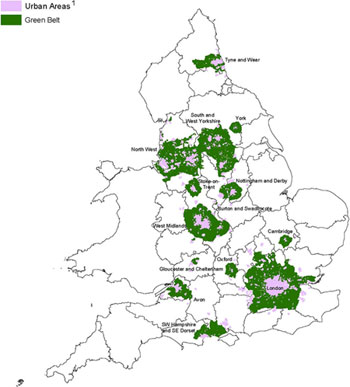

Distance, Density and Division matter.

Distance because of those transport costs, density because agglomeration raises productivity - cities are better for growth than the countryside, and artificial divisions raise costs of trade.

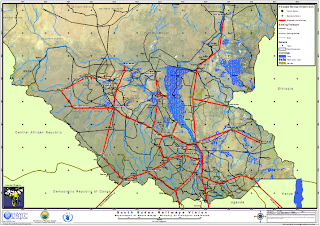

What does all this imply for Southern Sudan? At the moment market traders rely on both Khartoum and Uganda.

There are 2 key policy messages from the report - infrastructure and trade barriers.

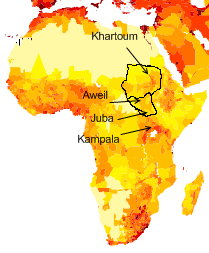

The strategic question is how much the South chooses to orientate itself towards integration with the Khartoum, and how much with the East African Community. The goal is to make links through improved transport and reduced administrative barriers to a successful agglomeration. At the moment there aren't any passable roads from the South to the North, so goods get flown in. Goods from Uganda and Kenya do get brought in by road.

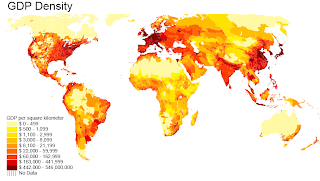

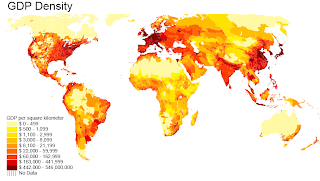

One way to think about this is Sachs'

GDP density, which basically gives you a map of where these agglomerations are.

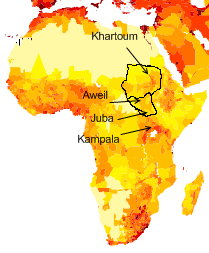

Zooming in on Africa, its pretty clear that Lake Victoria is where all the action is at. This is pretty convenient for Juba which is only just across the Ugandan border, but not so much for the big towns like Aweil in Bahr el Ghazal, which are closer to Khartoum than Kampala.

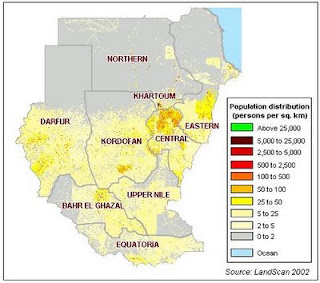

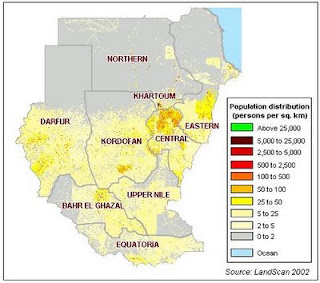

This idea is also reflected in the raw population densities - far more people around Lake Victoria than in Khartoum (Addis also has a lot of people, but there are some mountains in the way).

.jpg)

Trouble is that it seems from what weak data there is that the largest agglomeration in Southern Sudan is also the furthest from the Ugandan border, in Northern Bahr el Ghazal.

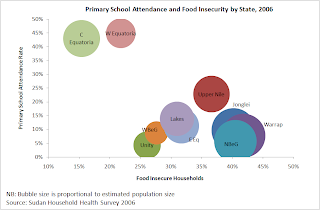

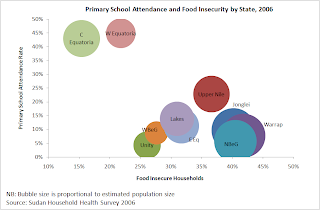

And unsurprisingly it is Central and Western Equatoria next to the Ugandan border that are doing the best, and the more populous States in Bahr el Ghazal and Upper Nile that are doing the worst.

.jpg)