Public support in rich countries for global development is critical for sustaining effective government and individual action. But the causes of public support are not well understood. Temporary migration to developing countries might play a role in generating individual commitment to development, but finding exogenous variation in travel with which to identify causal effects is rare. In this paper I address this question using a natural experiment - the assignment of Mormon missionaries to two year missions in different world regions - and test whether the attitudes and activities of returned missionaries differ. Data comes from a unique survey gathered on Facebook. Missionaries assigned to treat regions (Africa, Asia, Latin America) are balanced with those assigned to the control region (Europe) on high school test scores and prior language and travel experience. Those assigned to the treatment region report greater interest in global development and poverty, but no difference in support for government aid or higher immigration, and no difference in personal international donations, volunteering, or other involvement.Here's the link to the paper and the twitter discussion.

16 January 2025

Does temporary migration from rich to poor countries cause commitment to development?

23 November 2024

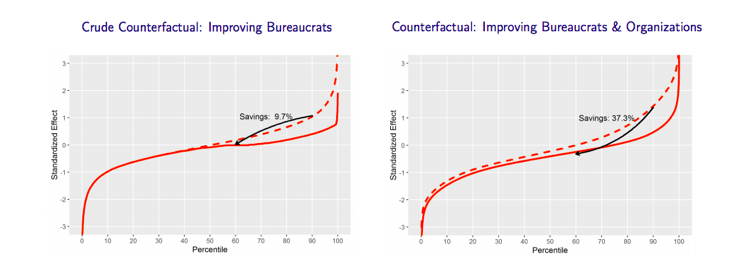

Innovations in Bureaucracy

The World Bank might be a bit more ahead of the curve here, and held a workshop earlier this month on “Innovating Bureaucracy.” I wasn’t able to attend (ahem, wasn’t invited), and so as the king of conference write-upsdoesn’t seem to have gotten around to it yet, I’ve written up my notes from skimming through the slides (you can read the full presentations here).

Tim Besley — state effectiveness now lies at the heart of the study of development. Incentives, selection, and culture are key, and it is essential to study the 3 together not in isolation.

Michael Best — looks at efficiency of procurement across 100,000 government agencies (each with decentralised hiring) in Russia. Wide variation in prices paid by different individuals/agencies, with big potential for improvement.

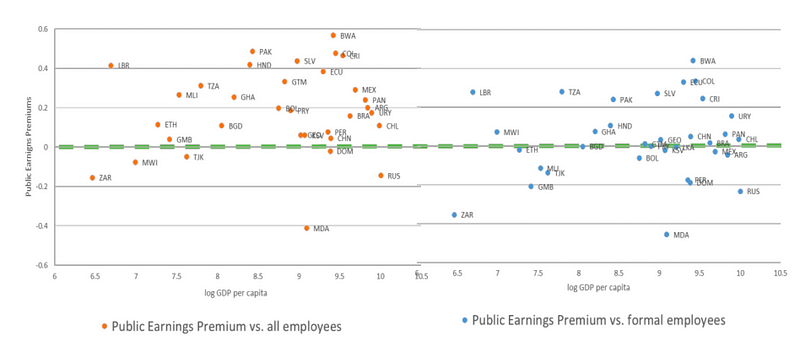

Zahid Hasnain — presents Worldwide Bureaucracy Indicators (WWBI) for 79 countries. Public sector employment is 60% of formal employment in Africa & South Asia, and is usually better paid than private employment.

Richard Disney — provides a critique of simple public-private pay gap comparisons — need to consider conditions, pensions, and vocation. Lack of well-identified causal studies.

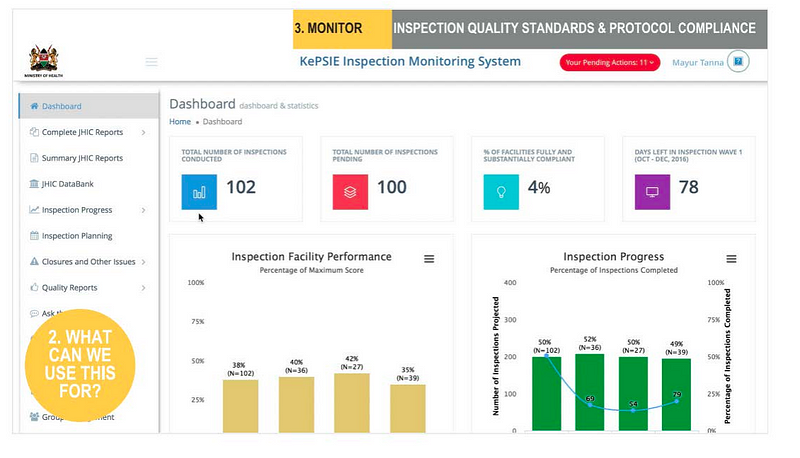

Arianna Legovini — improved inspections of health facilities in Kenya seem to be improving patient safety.

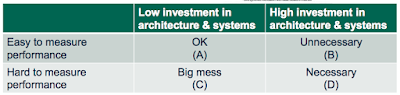

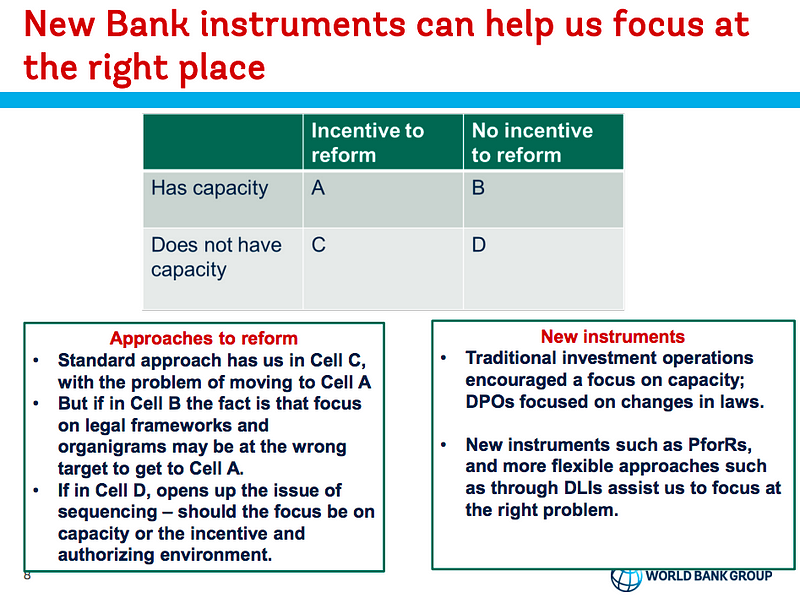

Jim Brumby, Raymond Muhula, Gael Rabelland — two helpful 2x2s — need to understand both capacity & incentive for reform, and then match data architecture to difficulty of measuring performance.

16 October 2024

Open Data for Education

The 2018 World Development Report makes clear the scale of the global learning crisis. Fewer than 1 in 5 primary school students in low income countries can pass a minimum proficiency threshold. The report concludes by listing 3 ideas on what external actors can do about it;

- Support the creation of objective, politically salient information

- Encourage flexibility and support reform coalitions

- Link financing more closely to results that lead to learning

And as expensive as they can be, surveys have limited value to policymakers as they focus on a limited sample and can only provide data about trends and averages, not individual schools. As my colleague Justin Sandefur has written; “International comparability be damned. Governments need disaggregated, high frequency data linked to sub-national units of administrative accountability.”

Even for research, much of the cutting edge education literature in advanced countries makes use of administrative not survey data. Professor Tom Kane (Harvard) has argued persuasively that education researchers in the US should abandon expensive and slow data collection for RCTs, and instead focus on using existing administrative testing and data infrastructure, linked to data on school inputs, for quasi-experimental analyses than can be done quickly and cheaply.

Can this work in developing countries?

My first PhD chapter (published in the Journal of African Economies) uses administrative test score data from Uganda, made available by the Uganda National Exams Board at no cost, saving data collection that would have cost hundreds of thousands of pounds and probably been prohibitively expensive. We’ve also analysed the same data to estimate the quality of all schools across the country, so policymakers can look up the effectiveness of any school they like, not just the handful that might have been in a survey (announced last week in the Daily Monitor).

Another paper I’m working on is looking at the Public School Support Programme (PSSP) in Punjab province, Pakistan. The staged roll-out of the program provides a neat quasi-experimental design that lasted only for the 2016-17 school year (the control group have since been treated). It would be impossible to go in now and collect retrospective test score data on how students would have performed at the end of the last school year. Fortunately, Punjab has a great administrative data infrastructure (though not quite as open as the website makes out), and I’m able to look at trends in enrolment and test scores over several years, and how these trends change with treatment by the program. And all at next to no cost.

For sure there are problems associated with using administrative data rather than independently collected data. As Justin Sandefur and Amanda Glassman point out in their paper, official data doesn’t always line up with independently collected survey data, likely because officials may have a strong incentive to report that everything is going well. Further, researchers don’t have the same level of control or even understanding about what questions are asked, and how data is generated. Our colleagues at Peas have tried to useofficial test data in Uganda but found the granularity of the test is not sufficient for their needs. In India there is not one but several test boards, who end up competing with each other and driving grade inflation. But not all administrative data is that bad. To the extent that there is measurement error, this only matters for research if it is systematically associated with specific students or schools. If the low quality and poor psychometric properties of an official test are just noisy estimates of true learning, this isn’t such a huge problem.

Why isn’t there more research done using official test score data? Data quality is one issue, but another big part is the limited accessibility of data. Education writer Matt Barnum wrote recently about “data wars” between researchers fighting to get access to public data in Louisiana and Arizona. When data is made easily available it gets used; a google scholar search for the UK “National Pupil Database” finds 2,040 studies.

How do we get more Open Data for Education?

Open data is not a new concept. There is an Open Data Charter defining what open means (Open by default, timely and comprehensive, accessible and usable, comparable and interoperable). The Web Foundation ranks countries on how open their data is across a range of domains in their Open Data Barometer, and there is also an Open Data Index and an Open Data Inventory.

Developing countries are increasingly signing up to transparency initiatives such as the Open Government Partnership, attending the Africa Open Data conference, or signing up to the African data consensus.

But whilst the high-level political backing is often there, the technical requirements for putting together a National Pupil Database are not trivial, and there are costs associated with cleaning and labelling data, hosting data, and regulating access to ensure privacy is preserved.

There is a gap here for a set of standards to be established in how governments should organise their existing test score data, and a gap for financing to help establish systems. A good example of what could be useful for education is the Agriculture Open Data Package: a collaboratively developed “roadmap for governments to publish data as open data to empowering farmers, optimising agricultural practice, stimulating rural finance, facilitating the agri value chain, enforcing policies, and promoting government transparency and efficiency.” The roadmap outlines what data governments should make available, how to think about organising the infrastructure of data collection and publication, and further practical considerations for implementing open data.

Information wants to be free. It’s time to make it happen.

05 September 2024

Why is there no interest in kinky learning?

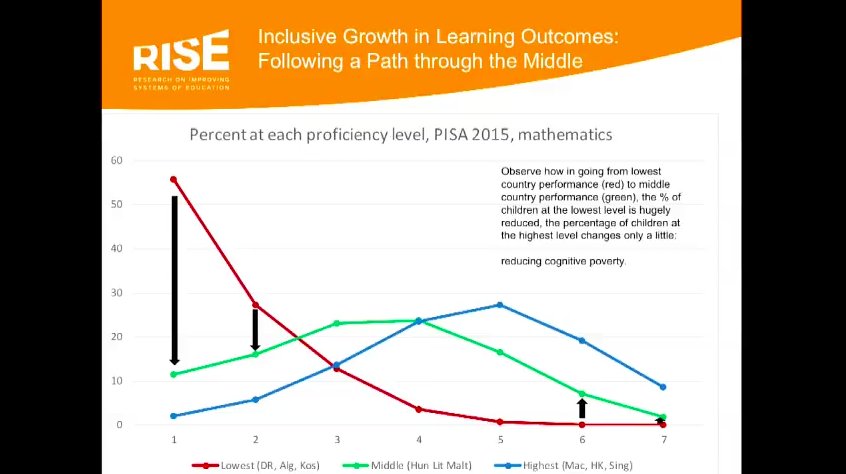

Weirdly, we have the opposite problem in global education, where it is impossible to get people to focus on small incremental gains for those at the bottom of the learning distribution. Luis Crouch gave a great talk at a RISE event in Oxford yesterday in which he used the term ‘cognitive poverty’ to define those at the very bottom of the learning distribution, below a conceptually equivalent (not yet precisely measured) ‘cognitive poverty line’. Using PISA data, he documents that the big difference between the worst countries on PISA and middling countries is precisely at the bottom of the distribution - countries with better average scores don’t have high levels of very low learning (level 1 and 2 on the PISA scale), but don’t do that much better at the highest levels.

Why have global poverty advocates been so successful at re-orientating an industry, but cognitive poverty advocates so unsuccessful?

28 April 2025

Top 10 Must-Read Articles on Education & Development

What should you read first if you’re a new policy advisor in a Ministry of Education? Here is my response to a couple of recent emails along these lines on the CGD blog.

09 October 2024

Does foreign aid harm political institutions?

Good news for reflective aid business -types who like agonising about what the point of it all is and sometimes wondering whether we’re even making things worse (err... talking about a friend... not me...). Also even good news for developing countries I suppose.

A new paper in the Journal of Development Economics by Sam Jones & Finn Tarp* using new data on aid (from aiddata.org) and institutions (from the Quality of Government Institute) finds no evidence that aid has undermined institutions on average, if anything there seems to be a positive relationship. I’m less confident in the positive findings than reassured that in *none* of their various different approaches is the relationship negative.

Now you’re probably thinking “what about the 2006 CGD review paper by Todd Moss, Gunilla Pettersson & Nicolas Van de Walle, described by Blattman as "the best summary I know of the evidence”, which concluded that aid could have a harmful effect on institutional development”? Well the word “could” is important there - that conclusion was somewhat speculative, and this new evidence from Jones & Tarp fills an important gap in terms of systematic quantitative evidence on this topic, and should probably shift your priors at least a little in that direction.

I wonder what Angus Deaton would say?

---

* Thanks to UNU-WIDER the paper is open-access, which is great for what it is, but obviously having public institutions pay private journal owners something greater than the cost of production isn’t an ideal long-run equilibrium, and we really need something that fundamentally shifts the whole publishing industry.

16 June 2025

Global Organ Trade

Here’s a great idea from Al Roth, the 2012 Economics Nobel Prize winner.

Al got his prize for developing his theoretical matching ideas into a computerized kidney exchange - so if you want to donate a kidney to a family member but you aren’t the right match, you can find another pair of people in the same situation from a different city and criss-cross the pairing, so both kidney transplants can go ahead.

In his new book (reviewed here by Alex Tabarrok), Al proposes extending the kidney exchange internationally.

"Mr. Roth, however, wants to go further. The larger the database, the more lifesaving exchanges can be found. So why not open U.S. transplants to the world? Imagine that A and A´ are Nigerian while B and B´ are American. Nigeria has virtually no transplant surgery or dialysis available, so in Nigeria patient A’ will die for certain. But if we offered a free transplant to him, and received a kidney for an American patient in return, two lives would be saved.

The plan sounds noble but expensive. Yet remember, Mr. Roth says, “removing an American patient from dialysis saves Medicare a quarter of a million dollars. That’s more than enough to finance two kidney transplants.” So offering a free transplant to the Nigerian patient can save money and lives. It’s hard to think of a better example of gains from trade (or a better PR coup for the U.S. on the world stage). Better matching with computerized markets is saving lives, but more than 100,000 people are still waiting for kidneys in the United States alone."

05 June 2025

Graduate Jobs in South Sudan

"International development work is generally best done by people of the country in question: there is no shortage of talent in and from any of Somalia, South Sudan, DRC, or any other FCAS place you might name, only the conditions in which it might be deployed and developed.

But there is still a role in development work for people from the Global North if they have the right skills, the humility, understanding and connection to apply them well where they are sent, and hopefully the intention to continue to apply them in this work for the medium term. That doesn’t just mean water engineers and hard-bitten Treasury hands, it can also mean the high-achieving, high-potential generalists/fast-streamers that any organisation, the world over, would be glad to have.

But for those bright young people, getting into international development is not always straightforward: it can seem unwise to set off to a fragile state with no particular fixed plan, as many of those now working in this sector first did; getting to, and staying in, some of the places we work is expensive even if you do have systems already set up, let alone if you’re doing this the first time, straight out of College.

This Autumn, we are therefore going to be looking to hire up to six CGA Fellows to send to South Sudan, who will be either immediate or fairly recent graduates."

25 May 2025

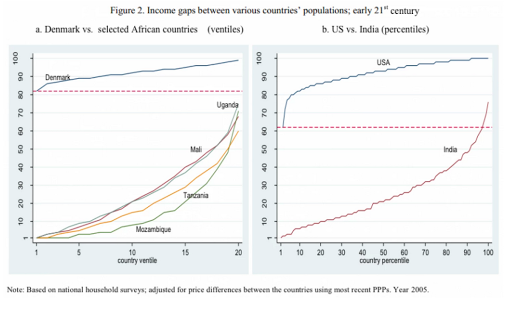

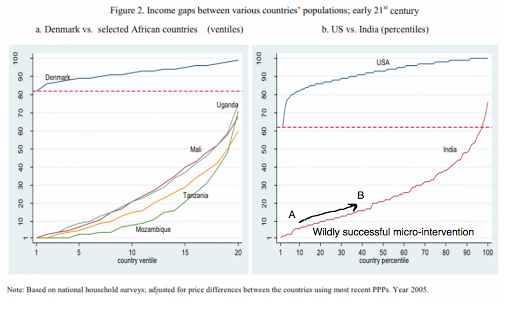

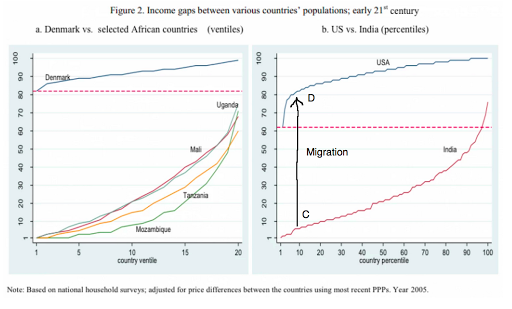

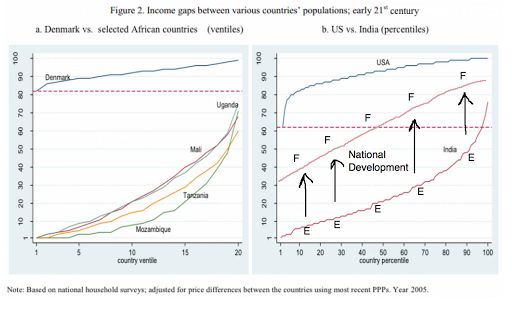

National Development vs Poverty Reduction, in charts

These charts by Branko Milanovic deserve looking at again and again. A few years ago Adrian Wood told my entire economics class to print off the Angus Maddison long-run world GDP chart and stick it on our walls so we’d look at it every day. I’d suggest adding the Milanovic chart alongside it.

I was struck earlier today (whilst listening to the latest Development Drums) how these charts could be used to illustrate the comparison between anti-poverty programs and National development that Lant talks about.

Projects to increase an individual’s income in developing countries can help people get a better livelihood amongst those available in that country, but they probably aren’t going to change the overall set of opportunities facing people living in a country. If you want to earn yourself rich, you need to sell stuff to rich people - that means exporting goods or services to rich countries (trade), moving to a rich country to sell your labour (migration), or encouraging rich people to come visit your country (tourism).

Graphically, the most successful ever anti-poverty program might at best move a bunch of people from point A to point B.

By comparison, migrating lets someone move from point C to point D.

And for something truly transformative, national development, probably based on exports, allows the whole country to shift up from E to F.

Anti-poverty programs can’t solve poverty.

17 March 2025

Labour Beyond Aid

How does it measure up?

CGD looks at 7 components of "Commitment to Development" in the annual index; aid, trade, migration, security, environment, technology, and finance.

Labour's pamphlet talks extensively about 2 of the 6 non-aid components of the index: the environment and security.

There is next to nothing on trade, migration, technology, and finance.

Out of 26 countries, the UK ranks 4th overall which is pretty good. Though that varies a lot between the components; Aid (4), Trade (7), Finance (2), Migration (13), Environment (11), Security (7), Technology (20).

There's more to International Development than Aid, but also more than climate change and security.

The Emerging Middle Class in Africa

It's a snip on Amazon at only £27.99, or you can read it on Google Books here.

I'm not sure which is my favourite review;

"This book is uplifting, methodologically and intellectually sound, and rich in policy prescriptions. A must read for researchers, educators, policy makers, and global partners. As AERC (www.aercafrica.org) Executive Director, I am heartened by this policy and intellectually rich book"

-Lemma W. Senbet, Professor and Executive Director, African Economic Research Consortium and The William E. Mayer Chair Professor of Finance, University of Maryland, USA

"a timely topic, by genuine experts" -Paul Collier, University of Oxford, UKCheers Paul.

11 March 2025

"I didn't come into politics to distribute money to people in the Third World!"

16 February 2025

Lampedusa Update

15 November 2024

Why be a consultant (with Mokoro)?

"Martin Adams never set out to be a consultant, but found himself stuck in an office job and so decided to go freelance ‘in places where I wanted to be and with people I liked.’ For him, this is the most rewarding part of being a consultant. For Liz Daley, ‘consultancy enables you to be your own boss and work flexibly and independently. This is a great asset if you have other responsibilities that you are very committed to - like being a parent in my case. It gives you variety of assignments and clients, which is good for intellectual stimulation. But, the big downside, it can be very isolating. And there is constant uncertainty financially, worrying about where the next piece of work will come from.’ Catherine Dom likes the flexibility and independence that the consultancy life offers and has been fortunate to have developed long-term relationships with a number of countries and people in them. For Chris Tanner, initially ‘consultancy allowed me to get a vast depth of experience in several places far more quickly than a ‘proper job’ would have done. The strong point of being a consultant is on the technical side for sure.’ Now returning to consultancy after a long stint with FAO in Mozambique, it ‘allows me to use my experience and to work in a way that is flexible and still keep my feet under the table in Wales.’ Stephen Turner drifted into consultancy, finds it ‘stimulating and stressful, perhaps especially for a generalist like me’, but also depressing because you can work hard on a project and yet get zero feedback."From Robin Palmer's reflections on his career. One part of my lack of blogging steam has been the takeover of twitter as a quicker way of sharing interesting snippets, but twitter is much less useful for me as a way of quickly finding the interesting clippings that I remember reading months ago and want to find again, so maybe expect more of this cutting and pasting.

15 July 2025

This is why I don't care about climate change

Poverty reduction tends to be strongly linked to economic growth, but growth impacts the environment and increases CO2 emissions. So can greener growth that is more climate-resilient and less environmentally damaging deliver large scale poverty reduction? ... We argue that there are bound to be trade-offs between emissions reductions and a greener growth on the one hand, and growth that is most effective in poverty reduction. We argue that development aid, earmarked for the poorest countries, should only selectively pay attention to climate change, and remain focused on fighting current poverty reduction, including via economic growth, not least as future resilience of these countries and their population will depend on their ability to create wealth and build up human capital now. The only use for development aid within the poorest countries for explicit climate-related investment ought to be when the investments also contribute to poverty reduction now

08 May 2025

DevBalls - Exposing the absurdities of the aid industry

"DevBalls is an online space for comment on the international development aid industry.

DevBalls is here because the aid industry has - functionally and morally - lost its way. And those who should hold it to account - the media, researchers, politicians - don’t. DevBalls is here because aid can only become better when its absurdities and hypocrisies are open to view.

DevBalls is compiled by a group of aid professionals who control its content. We welcome relevant contributions sent to [email protected]. Anonymity is guaranteed."

15 April 2025

Do teachers skip class because of low pay?

The 2014 Education for All Global Monitoring Report, which was launched in London last week, puts the problem mainly down to the low pay and poor working conditions of teachers.

"While teacher absenteeism and engagement in private tuition are real problems, policy-makers often ignore underlying reasons such as low pay and a lack of career opportunities. ... Policy-makers need to understand why teachers miss school. In some countries, teachers are absent because their pay is extremely low, in others because working conditions are poor. In Malawi, where teachers’ pay is low and payment often erratic, 1 in 10 teachers stated that they were frequently absent from school in connection with financial concerns, such as travelling to collect salaries or dealing with loan payments. High rates of HIV/AIDS can take their toll on teacher attendance."The report includes this chart, showing that in a handful of countries teachers earn below $10 a day (which they have decided is not enough to live on).

Which seems jarring when the same week there was a conference on the economics of education in developing countries, where much of the literature is focused exactly on this issue of teacher absenteeism, and finds very little evidence that low pay is the main factor (as opposed to, say, weak or non-existent systems of accountability). In India it is well documented that whereas absenteeism is roughly similar in public and private schools, teachers in public schools are paid more than 5 times as much as private school teachers.

(See for example this chart from data from Singh 2013, or similar from Kremer et al 2005, Alcazar et al 2006 in Peru, or African data here)

"There is very little evidence that higher salaries lead to better attendance, however. Contract teachers have the same or higher absence rates. Compared to public school teachers, though, private school teachers are absent less, even though contract and private school teachers alike take home much less pay than their regular civil service public school teacher counterparts."As little as teachers might make in some countries, they are still doing well relative to most other people. In many countries public primary school teachers are the 1%.

I thought I'd take a quick look at the data presented in the GMR and see what those teacher salaries are presented as a % of GDP. In OECD countries, average teacher salary is roughly around the same level as GDP per capita. In African countries, the average teacher salary is 3 - 4 times GDP per capita.

Karthik Muralidharan summarised the state of public schools in India as facing two problems; governance and pedagogy. This probably generalises to much of the developing world. What this GMR comes across as doing is focusing almost entirely on the pedagogy problem, and sweeping the governance problem under the carpet (receiving roughly 10 pages attention out of a 300 page report). Perhaps this is a welcome counterbalance to prominent World Bank research which focuses much more on the governance problem. But really shouldn't a major flagship state of the sector report aspire to properly tackle both? Of course fixing the pedagogy problem means working with teachers to improve their capabilities and not demonising them or calling them all lazy slackers. But neither can we just ignore the reality of skiving on a massive scale (or: Don't hate the player, hate the game).

03 April 2025

What do (cutting-edge, leading, academic) development economists do?

"The Chief Minister posed serious questions that have traditionally been the bread and butter of the economics profession. Unfortunately, we are not even trying to answer them any more. The specific question was “Should I put more money into transport? Infrastructure (power, roads, water)? Law and order? Social services? Or what? And where am I going to get the money?” What questions could be more solidly part of the core of economics than these? Unfortunately none of these were even remotely the focus of the “evidence-based” policy making discussed.

Almost all of the cases analyzed were single, simple policy “tweaks” that were, first of all, isolated from the broader market context in which they occurred and, second, had no conception of opportunity cost - what we would have to give up to pursue these things?"

27 February 2025

Development as... no measurable increase in happiness

And happiness? Nothing. No change at all. Maybe a bit of a drop. Measured across three different surveys. Chew on that one.