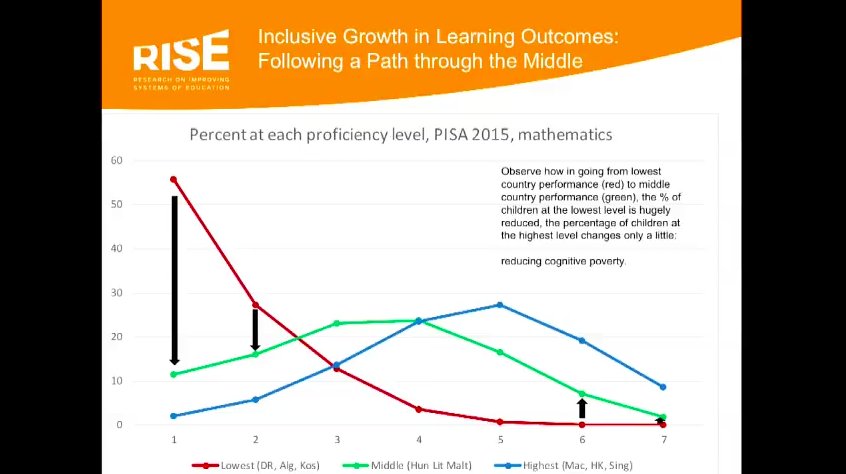

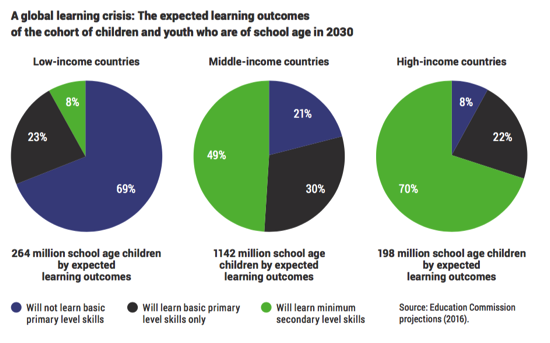

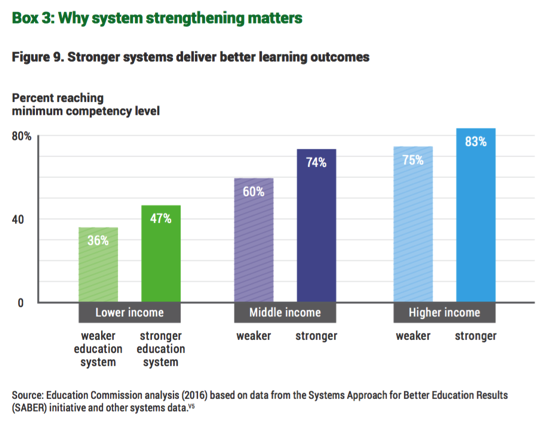

makes clear the scale of the global learning crisis. Fewer than 1 in 5 primary school students in low income countries can pass a minimum proficiency threshold. The report concludes by listing 3 ideas on what external actors can do about it;

- Support the creation of objective, politically salient information

- Encourage flexibility and support reform coalitions

- Link financing more closely to results that lead to learning

The first of these, generating new information about learning, can be expensive. Travelling up and down countries to sit and test kids for a survey can cost a lot of money. The average RCT costs in the range of $0.5m. Statistician

Morten Jerven added up the costs of establishing the basic census and national surveys necessary to measure the SDGs — coming to a total of $27 billion per year, far more than is currently spent on statistics.

And as expensive as they can be, surveys have limited value to policymakers as they focus on a limited sample and can only provide data about trends and averages, not individual schools. As my colleague Justin Sandefur has written; “International comparability be damned. Governments need disaggregated, high frequency data linked to sub-national units of administrative accountability.”

Even for research, much of the cutting edge education literature in advanced countries makes use of administrative not survey data. Professor

Tom Kane (Harvard) has argued persuasively that education researchers in the US should abandon expensive and slow data collection for RCTs, and instead focus on using existing administrative testing and data infrastructure, linked to data on school inputs, for quasi-experimental analyses than can be done quickly and cheaply.

Can this work in developing countries?

My first PhD chapter (published in the Journal of African Economies) uses administrative test score data from Uganda, made available by the Uganda National Exams Board at no cost, saving data collection that would have cost hundreds of thousands of pounds and probably been prohibitively expensive. We’ve also analysed the same data to estimate the quality of all schools across the country, so policymakers can look up the effectiveness of any school they like, not just the handful that might have been in a survey (announced last week in the Daily Monitor).

Another paper I’m working on is looking at the Public School Support Programme (PSSP) in Punjab province, Pakistan. The staged roll-out of the program provides a neat quasi-experimental design that lasted only for the 2016-17 school year (the control group have since been treated). It would be impossible to go in now and collect retrospective test score data on how students would have performed at the end of the last school year. Fortunately, Punjab has a great administrative data infrastructure (though not quite as open as the website makes out), and I’m able to look at trends in enrolment and test scores over several years, and how these trends change with treatment by the program. And all at next to no cost.

For sure there are problems associated with using administrative data rather than independently collected data. As Justin Sandefur and Amanda Glassman point out in their paper, official data doesn’t always line up with independently collected survey data, likely because officials may have a strong incentive to report that everything is going well. Further, researchers don’t have the same level of control or even understanding about what questions are asked, and how data is generated. Our colleagues at Peas have tried to useofficial test data in Uganda but found the granularity of the test is not sufficient for their needs. In India there is not one but several test boards, who end up competing with each other and driving grade inflation. But not all administrative data is that bad. To the extent that there is measurement error, this only matters for research if it is systematically associated with specific students or schools. If the low quality and poor psychometric properties of an official test are just noisy estimates of true learning, this isn’t such a huge problem.

Why isn’t there more research done using official test score data? Data quality is one issue, but another big part is the limited accessibility of data. Education writer Matt Barnum wrote recently about “

data wars” between researchers fighting to get access to public data in Louisiana and Arizona. When data is made easily available it gets used; a

google scholar search for the UK “National Pupil Database” finds 2,040 studies.

How do we get more Open Data for Education?

Open data is not a new concept. There is an

Open Data Charter defining what open means (Open by default, timely and comprehensive, accessible and usable, comparable and interoperable). The Web Foundation ranks countries on how open their data is across a range of domains in their

Open Data Barometer, and there is also an Open Data Index and an

Open Data Inventory.

Developing countries are increasingly signing up to transparency initiatives such as the

Open Government Partnership, attending the Africa Open Data conference, or signing up to the African data consensus.

But whilst the high-level political backing is often there, the technical requirements for putting together a National Pupil Database are not trivial, and there are costs associated with cleaning and labelling data, hosting data, and regulating access to ensure privacy is preserved.

There is a gap here for a set of standards to be established in how governments should organise their existing test score data, and a gap for financing to help establish systems. A good example of what could be useful for education is the Agriculture Open Data Package: a collaboratively developed “roadmap for governments to publish data as open data to empowering farmers, optimising agricultural practice, stimulating rural finance, facilitating the agri value chain, enforcing policies, and promoting government transparency and efficiency.” The roadmap outlines what data governments should make available, how to think about organising the infrastructure of data collection and publication, and further practical considerations for implementing open data.

Information wants to be free. It’s time to make it happen.