And what do we even actually mean when we talk about accountability?

Perhaps the key theme emerging from research on reforming education systems is accountability. But accountability means different things to different people. To start with, many think first of bottom-up (‘citizen’ or ‘social’) accountability. But increasingly in development economics, enthusiasm is waning for bottom-up social accountability as studies show limited impacts on outcomes. The implicit conclusion then is to revisit top-down (state) accountability. As Rachel Glennerster (Executive Director of J-PAL)

wrote recently:

"For years the Bank and other international agencies have sought to give the poor a voice in health, education, and infrastructure decisions through channels unrelated to politics. They have set up school committees, clinic committees, water and sanitation committees on which sit members of the local community. These members are then asked to “oversee” the work of teachers, health workers, and others. But a body of research suggests that this approach has produced disappointing results."

One striking example of this kind of research is Ben Olken’s work on infrastructure in Indonesia, which directly compared the effect of a top-down audit (which was effective) with bottom-up community monitoring (ineffective).

So what do we mean by top-down accountability for schools?

Within top-down accountability there are a range of methods by which schools and teachers could be held accountable for their performance. Three broad types stand out:

- Student test scores (whether simple averages or more sophisticated value-added models)

- Professional judgement (e.g. based on lesson observations)

- Student feedback

The Gates Foundation published a major report in 2013 on how to “Measure Effective Teaching”, concluding that each of these three types of measurement has strengths and weaknesses, and that the best teacher evaluation system should therefore combine all three: test scores, lesson observations, and student feedback.

By contrast, when it comes to holding head teachers accountable for school performance, the focus in both US policy reform and research is almost entirely on test scores. There are good reasons for this - education in the US has developed as a fundamentally local activity built on bottom up accountability, often with small and relatively autonomous school districts, with little tradition of supervision by higher levels of government. Nevertheless, as Helen Ladd, a Professor of Public Policy and Economics at Duke University and an expert in school accountability, wrote on the Brookings blog last year:

"The current test based approach to accountability is far too narrow … has led to many unintended and negative consequences. It has narrowed the curriculum, induced schools and teachers to focus on what is being tested, led to teaching to the test, induced schools to manipulate the testing pool, and in some well-publicized cases induced some school teachers and administrators to cheat.

Now is the time to experiment with inspections for school accountability …

Such systems have been used extensively in other countries … provide useful information to schools … disseminate information on best practices … draw attention to school activities that have the potential to generate a broader range of educational outcomes than just performance on test scores … [and] treats schools fairly by holding them accountable only for the practices under their control …

The few studies that have focused on the single narrow measure of student test scores have found small positive effects."

A

report by the US think tank “Education Sector” also highlights the value of feedback provided through inspection systems to schools.

"Like many of its American counterparts, Peterhouse Primary School in Norfolk County, England, received some bad news early in 2010. Peterhouse had failed to pass muster under its government’s school accountability scheme, and it would need to take special measures to improve. But that is where the similarity ended. As Peterhouse’s leaders worked to develop an action plan for improving, they benefited from a resource few, if any, American schools enjoy. Bundled right along with the school’s accountability rating came a 14-page narrative report on the school’s specific strengths and weaknesses in key areas, such as leadership and classroom teaching, along with a list of top-priority recommendations for tackling problems. With the report in hand, Peterhouse improved rapidly, taking only 14 months to boost its rating substantially."

In the UK, ‘

Ofsted’ reports are based on a composite of several different dimensions, including test scores, but also as importantly, independent assessments of school leadership, teaching practices and support for vulnerable students.

There is a huge lack of evidence on school accountability

This blind spot on school inspections isn’t just a problem for education in the US, though. The US is also home to most of the leading researchers on education in developing countries, and that research agenda is skewed by the US policy and research context. The leading education economists don’t study inspections because there aren’t any in the places they live.

The best literature reviews in economics can often be found in the “Handbook of Economics” series and the Journal of Economic Perspectives (JEP). The Handbook article on "

School Accountability" from 2011 exclusively discusses the kind of test-based accountability that is common in the US, with no mention of the kind of inspections common in Europe and other countries at all. A recent JEP symposium on Schools and Accountability includes a great article by Isaac Mbiti, a Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) researcher, on ’

The Need for Accountability in Education in Developing Countries” which includes; however, only one paragraph on school inspections. Another great resource on this topic is the 2011 World Bank book, "

Making Schools Work: New Evidence on Accountability Reforms”. This 'must-read' 250-page book has only two paragraphs on school inspections.

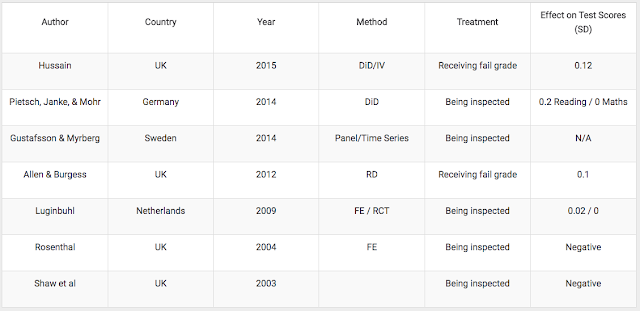

This is in part a disciplinary point - it is mostly a blind-spot of economists. School inspections have been studied in more detail by education researchers. But economists have genuinely raised the bar in terms of using rigorous quantitative methods to study education. In total, I count 7 causal studies of the effects of inspections on learning outcomes - 3 by economists and 4 by education researchers.

Putting aside learning outcomes for a moment,

one study from leading RISE researchers, Karthik Muralidharan and Jishnu Das (with Alaka Holla and Aakash Mohpal), in rural India finds that “increases in the frequency of inspections are strongly correlated with lower teacher absence”, which could be expected to lead to more learning as a result. However, no such correlation was found for other countries in a

companion study (Bangladesh, Ecuador, Indonesia, Peru, and Uganda).

There is also

fascinating qualitative work by fellow RISE researcher, Yamini Aiyar (Director of the ‘Accountability Initiative’ and collaborator of RISE researchers Rukmini Banerji, Karthik Muralidharan, and Lant Pritchett) and co-authors, that looks into how local level education administrators view their role in the Indian state of Bihar. The most frequently used term by local officials to describe their role was a “Post Officer” - someone who simply passes messages up and down the bureaucratic chain - “a powerless cog in a large machine with little authority to take decisions." A survey of their time use found that on average a school visit lasts around one hour, with 15 minutes of that time spent in a classroom, with the rest spent “checking attendance registers, examining the mid-day meal scheme and engaging in casual conversations with headmasters and teacher colleagues … the process of school visits was reduced to a mechanical exercise of ticking boxes and collecting relevant data. Academic 'mentoring' of teachers was not part of the agenda.”

At the Education Partnerships Group (EPG) and RISE we’re hoping to help fill this policy and research gap, through nascent school evaluation reforms supported by EPG in Madhya Pradesh, India, that will be studied by the RISE India research team, and an ongoing reform project working with the government of the Western Cape in South Africa. Everything we know about education systems in developing countries suggests that they are in crisis, and that a key part of the solution is around accountability. Yet we know little about how school inspections - the main component of school accountability in most developed countries - might be more effective in poor countries. It’s time we changed that.

This post appeared first on the RISE website.