11 March 2025

The Latest Economics Research on Global Education

06 February 2025

CfEE Blogging: Giving students information on future wages improves school outcomes

Did you know what career you wanted to do when you were in secondary school? I didn’t. Most pupils make critically important choices that will affect their lives throughout their educational career, often on the basis of poor information about what those choices will mean for their future. In most countries, there is little transparency on the costs and benefits of pursuing education and information on the various career paths available.

In this paper, Ciro Avitabile and Rafael de Hoyos study whether or not providing pupils with better information about the earnings returns to education and the options available lead to greater effort and learning. Several studies have previously shown that providing information about the wage gains from schooling leads pupils to stay in school a bit longer, and affects their educational choices, but there is limited evidence that such information can affect learning per se, at least in a slightly longer-term perspective.

16 January 2025

Does temporary migration from rich to poor countries cause commitment to development?

Public support in rich countries for global development is critical for sustaining effective government and individual action. But the causes of public support are not well understood. Temporary migration to developing countries might play a role in generating individual commitment to development, but finding exogenous variation in travel with which to identify causal effects is rare. In this paper I address this question using a natural experiment - the assignment of Mormon missionaries to two year missions in different world regions - and test whether the attitudes and activities of returned missionaries differ. Data comes from a unique survey gathered on Facebook. Missionaries assigned to treat regions (Africa, Asia, Latin America) are balanced with those assigned to the control region (Europe) on high school test scores and prior language and travel experience. Those assigned to the treatment region report greater interest in global development and poverty, but no difference in support for government aid or higher immigration, and no difference in personal international donations, volunteering, or other involvement.Here's the link to the paper and the twitter discussion.

15 January 2025

Testing, testing: the 123's of testing

"teachers tend to oppose standardised tests, partly because they perceive them to narrow the curriculum and crowd out wider learning. However, it is intuitive that the effects of testing could vary dramatically by context. Indeed, the impact may very well follow a so-called “Laffer curve”. At low levels of testing, an increase may lead to better performance as it provides relevant information and incentives to actors in the education system. Yet if there are already high levels of testing, further increases may very well decrease performance, due to stress, for example, or the effects of an overly-narrowed curriculum. If so, we should expect the impact of testing to follow an inverted U-curve - or at the very least display diminishing returns. Furthermore, the impact of tests is also likely to depend on exactly how they are used in the education system.

This paper provides perhaps the first systematic evidence on these issues"

20 September 2024

Probably the best new research in global education economics

The Digest is out today and I'm really pleased with how its come out, a fantastic set of blogs summarising a fascinating set of papers.

Here's the summary, and you can download the full report here.

30 November 2024

How to achieve public policy reform by surprise and confusion

"Well, one thing that did certainly affect it is the tactics of how to reform, in the sense that, certainly in academia, you are basically told you need to think deeply. Then there are a lot of pressure groups, lobbies, so you need to talk to them. You need to use the media for communicating the benefits of reform, and so on. Some of the reformers, successful reformers that I spoke with, before I joined the Bulgarian government, basically I said, 'You go, and on Day 1, you surprise everybody. So, you go in every direction you can, because they will be confused what's happening and you may actually be successful in some of the reforms. So, this is what I did. I went to Bulgaria in late July 2009; the Eurozone Crisis had already started around us. Greece was just about to collapse a few months later. So, there was kind of a feeling that something is to happen. But, instead of going, 'Let's now do labor reform,' then, 'Let's do business entry reform,' in the government we literally went 6 or 7 different directions hoping that Parliament will be, you know, confused or too happy to be elected--they were just elected. And we actually succeeded in most of these reforms. When I tried to do meaningful, well-explained reforms two years after, they all got bogged down, because lobbying will essentially take over and, 'Not now; let's wait for next year's government,' and so on."From the always interesting Econ Talk.

23 November 2024

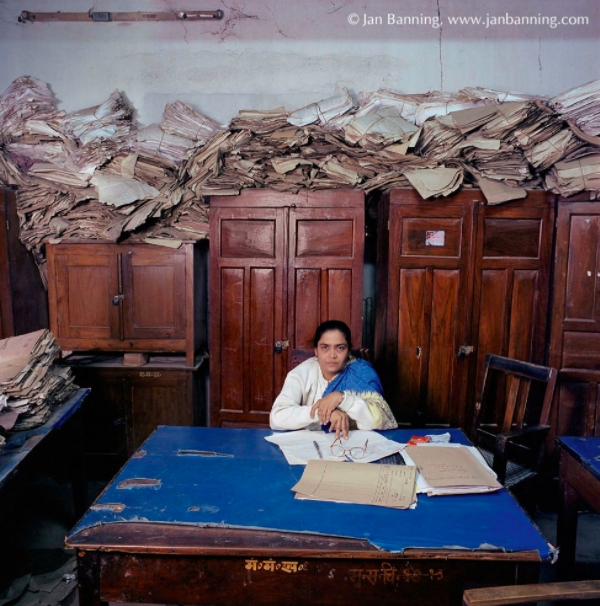

Innovations in Bureaucracy

The World Bank might be a bit more ahead of the curve here, and held a workshop earlier this month on “Innovating Bureaucracy.” I wasn’t able to attend (ahem, wasn’t invited), and so as the king of conference write-upsdoesn’t seem to have gotten around to it yet, I’ve written up my notes from skimming through the slides (you can read the full presentations here).

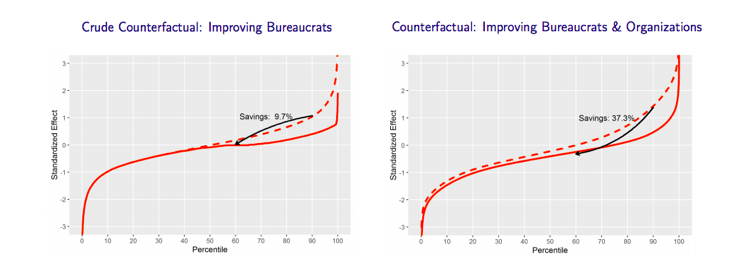

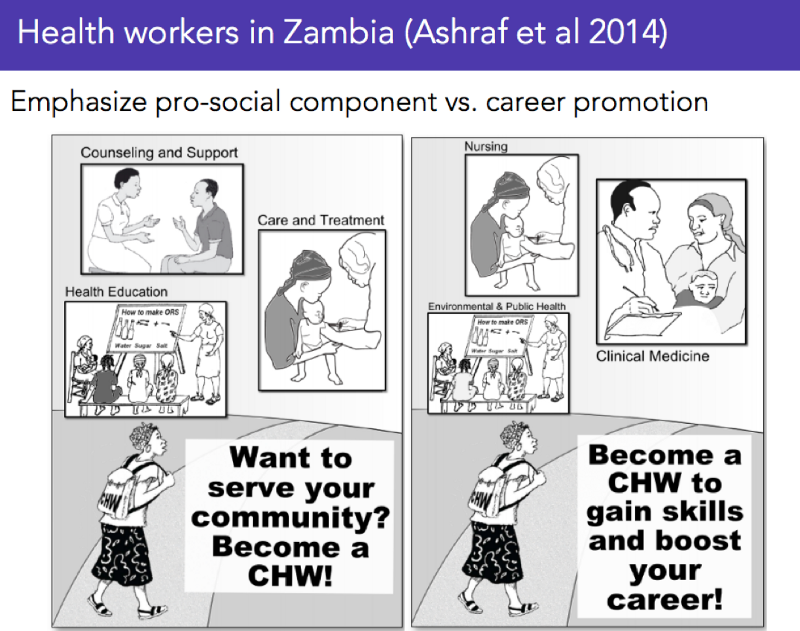

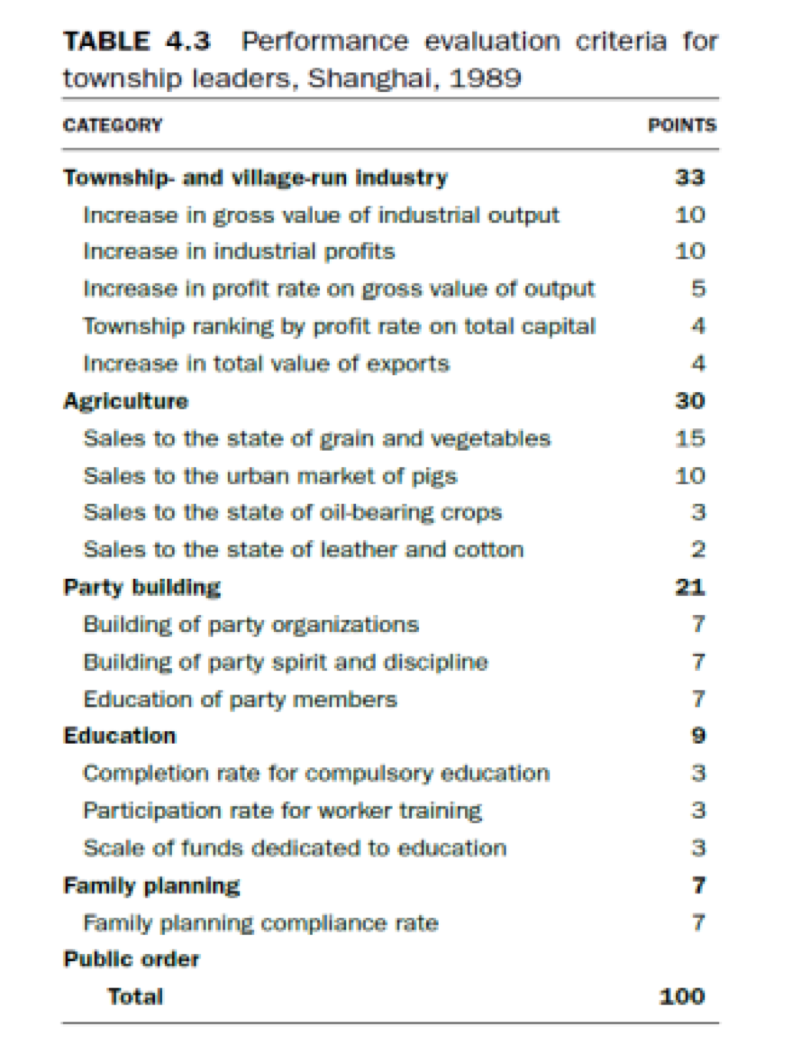

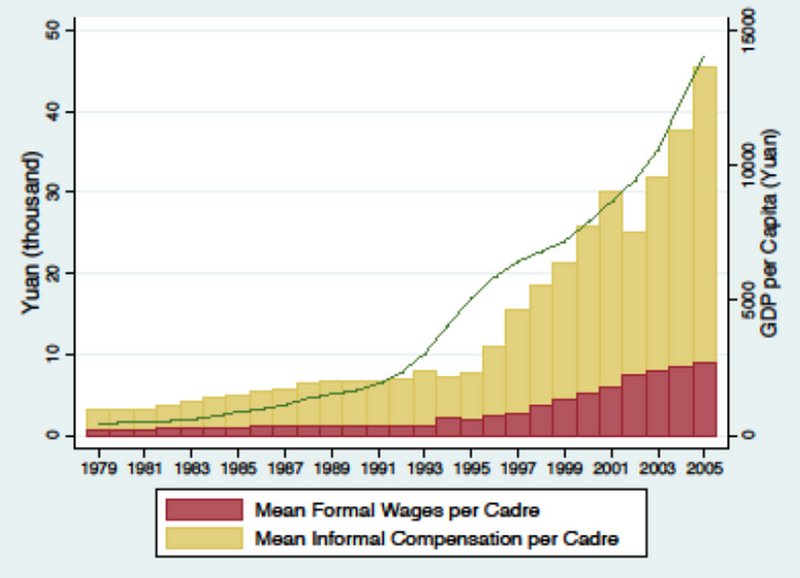

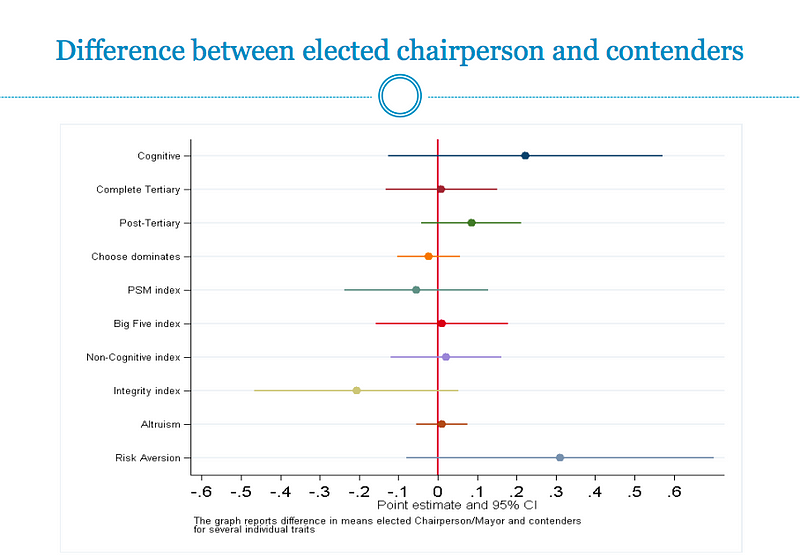

Tim Besley — state effectiveness now lies at the heart of the study of development. Incentives, selection, and culture are key, and it is essential to study the 3 together not in isolation.

Michael Best — looks at efficiency of procurement across 100,000 government agencies (each with decentralised hiring) in Russia. Wide variation in prices paid by different individuals/agencies, with big potential for improvement.

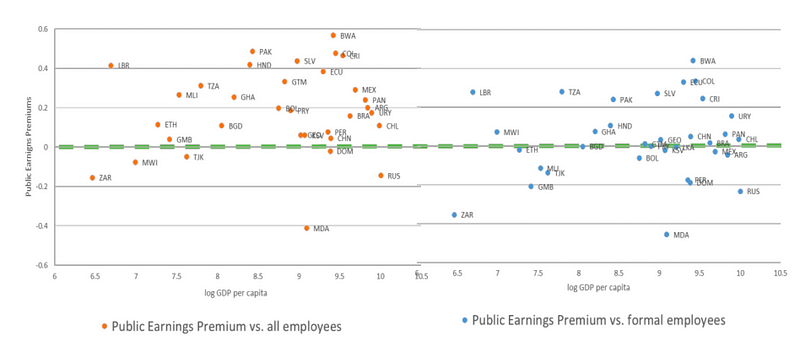

Zahid Hasnain — presents Worldwide Bureaucracy Indicators (WWBI) for 79 countries. Public sector employment is 60% of formal employment in Africa & South Asia, and is usually better paid than private employment.

Richard Disney — provides a critique of simple public-private pay gap comparisons — need to consider conditions, pensions, and vocation. Lack of well-identified causal studies.

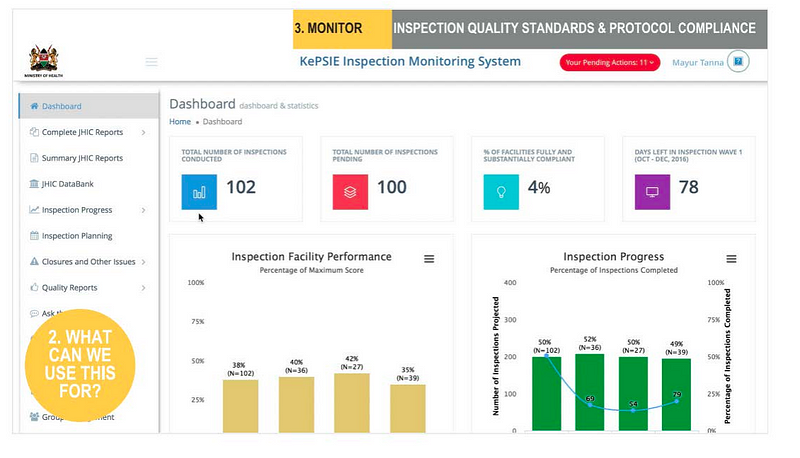

Arianna Legovini — improved inspections of health facilities in Kenya seem to be improving patient safety.

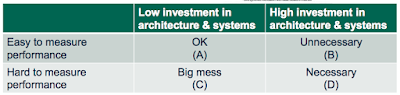

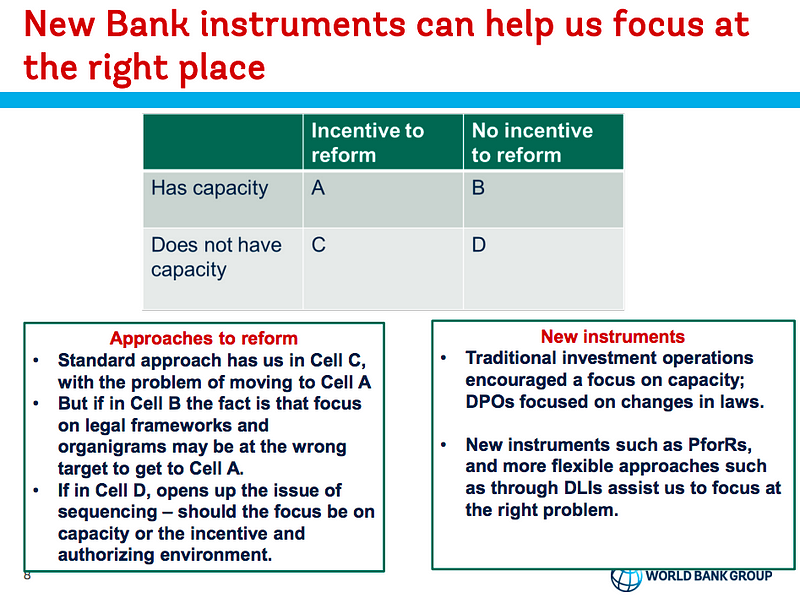

Jim Brumby, Raymond Muhula, Gael Rabelland — two helpful 2x2s — need to understand both capacity & incentive for reform, and then match data architecture to difficulty of measuring performance.

11 October 2024

Why don’t parents value school effectiveness? (because they think LeBron’s coach is a genius)

A new NBER study exploits the NYC centralised school admissions database to understand how parents choose which schools to apply for, and finds (shock!) parents choose schools based on easily observable things (test scores) rather than very difficult to observe things (actual school quality as estimated (noisily!) by value-added).

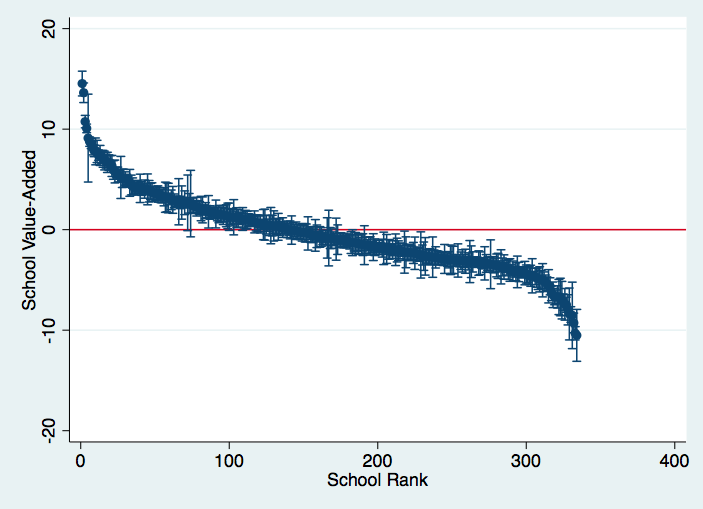

Value-added models are great — they’re a much fairer way of judging schools than just looking at test scores. Whilst test scores conflate what the student’s home background does with what the school does, value-added models (attempt to) control for a student’s starting level (and therefore all the home inputs up that point), and just looking at the progress that students make whilst at a school.

David Leonhardt put in well;

“For the most part, though, identifying a good school is hard for parents. Conventional wisdom usually defines a good school as one attended by high-achieving students, which is easy to measure. But that’s akin to concluding that all of LeBron James’s coaches have been geniuses.”Whilst value-added models are fairer on average, they’re typically pretty noisy for any individual school, with large and overlapping confidence intervals. Here’s the distribution of school value-added estimates for Uganda (below). There are some schools at the top and bottom that are clearly a lot better or worse than average (0), but there are also a lot of schools around the middle that are pretty hard to distinguish from each other, and that is using an econometric model to analyse hundreds of thousands of data points. A researcher or policymaker who can observe the test score of every student in the country can’t distinguish between the actual quality of many pairs of schools, and we expect parents to be able to do so on the basis of just a handful of datapoints and some kind of econometric model in their head??

Making school quality visible

If parents don’t value school effectiveness when it is invisible, what happens if we make it visible by publishing data on value-added? There are now several studies looking at the effect of providing information to parents on test score levels, finding that parents do indeed change their behaviour, but there are far fewer studies directly comparing the provision of value-added information with test score levels.

One study from LA did do this, looking at the effect of releasing value-added data compared to just test score levels on local house prices, finding no additional effect of providing the value-added data. But this might just be because not enough of the right people accessed the online database (indeed, another study from North Carolina found that providing parents with a 1-page sheet with information that had already been online for ages already still caused a change in school choice).

It is still possible that publishing and properly targeting information on school effectiveness might change parent behaviour.

Ultimately though, we’re going to keep working on generating value-added data with our partners because even if parents don’t end up valuing the value-added data, there are two other important actors who perhaps might — the government when it is considering how to manage school performance, and the school themselves.

14 February 2025

LSE on the UK gov’s new housing plans

"The fundamental problems with housing remain the same as in the last fifteen years and of those the most fundamental is the lack of land for development. Only fundamental reforms of our housing supply process will help and this proposes none. Indeed it in some ways goes backwards. It goes from a set of (not very good) mechanisms delivered in 2007 with the Regional Spatial Strategies to a set of aspirational gestures. Frankly the Secretary of State could build more houses with a magic wand."From the Spatial Economics Research Centre blog

10 January 2025

Experimental Conversations

When I was studying for my undergraduate degree, probably the most enjoyable book I read I think I happened to stumble across in the library (back in the day when you had to actually go to the library to find book chapters and physical copies of journals to read), called ‘Conversations with Leading Economists’. The conversational style, discussing in conversational language how ideas came about and how theorists interacted with each others' ideas and with data, was an amazing breath of fresh air, and a world away from the weirdness of the textbooks which often appear to pass down strange and seemingly grossly unrealistic theories and models of the world as if they were some kind of natural law. The list of interviewees includes Milton Friedman, Robert Lucas, Gregory Mankiw, Franco Modigliani, Paul Romer, Robert Solow.

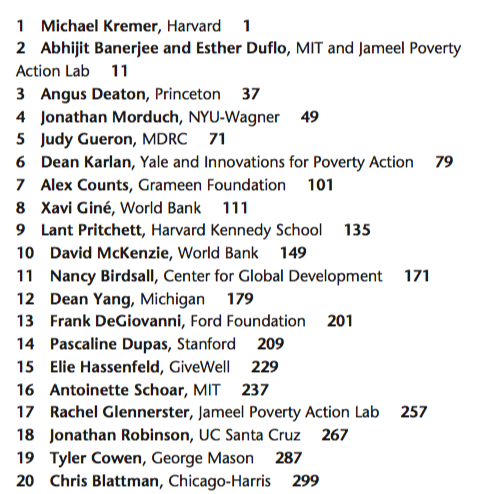

That conversational style can probably be slightly more commonly found these days in the post-blogging social media world, but there are still plenty of important thinkers who don’t very frequently blog or write op-eds (they’re busy being important thinkers), so Timothy Ogden has provided the wonderful service of writing up a series of interviews with some of the leading voices in both academia and policy on the use of randomized evaluations and field experiments in development economics.

You can buy the book 'Experimental Conversations’ here.

12 October 2024

How much of a jerk do you have to be oppose aid?

Angus Deaton wrote a few months ago about “Rethinking Robin Hood” (he was also on EconTalk a couple of days ago).

His argument is that a) the poorest in the US are maybe worse off than we think, and b) we should rethink the "cosmopolitan” ethical rule that places an equal weight on foreigners as co-nationals. Of course, he says, we shouldn’t totally disregard foreigners, we just have lower obligations to them, and greater obligations to people in the same nation as us. Which is all fine and everything, but its also a bit of a straw man. The interesting question, if we can agree that we have lower but not zero obligations to foreigners, is *how much* lower are our obligations to them?

In one of my favourite ever blog posts (now offline, but summarised on Dani Rodrik’s blog), the anonymous blogger “YouNotSneaky” calculates how much you have to value the welfare of a foreigner in order to oppose immigration (or “How much of a jerk do you have to be to oppose immigration”). The answer is you need to think that our obligation to foreigners is less than 1/20th of our obligation to co-nationals in order to oppose any immigration. Personally, I’m not at all comfortable with that low of a weight, but I suppose your mileage may vary.

In principle you could make some kind of similar calculation with regards to foreign aid, but I’m guessing that the less than 0.7% of GDP we so generously lavish on the global poor isn’t anything close to how much we would spend if we were actually really anywhere close to being "cosmopolitan prioritarians” and treating our obligations to foreigners as equal to those to co-nationals.

05 May 2025

Does “the Economist” know what a “market failure” is?

Apparently not. "Do British housing markets suffer from market failure”? The answer is no.

Here’s a quick refresher - a market failure is when the market - left alone - doesn’t produce an efficient or pareto optimal solution. Good examples are externalities such as pollution or congestion, or public goods such as new vaccines. The London housing market is not a good example of a market failure, where poor outcomes are the result of clumsy government regulation restricting supply. The fact that the market is responding to insane restrictions on new supply by focusing what little building they are allowed to do on expensive rather than affordable houses is not a market failure. Yes it is a market, and yes it is producing poor outcomes, but it is failing because of over-regulation. That is a government failure not a failure of the market mechanism.

It’s one thing when ordinary people use economic jargon in a colloquial sense with a totally different meaning to the economic term, but you expect better from a magazine called the Economist.

02 May 2025

A rare non-ideological argument against for-profit schools

To [Samuel] Abrams, the problem with for-profit operation of schools is not that businessmen are making money off the provision of a public service such as education. Textbook publishers, software developers, and bus operators all make money from schools and should, he said, but they are all providing a discrete good or service that can be easily evaluated. “School management, on the other hand, is a complex service that does not afford the transparency necessary for proper contract enforcement,” he said. “Without such transparency, there’s client distrust: parents, taxpayers, and legislators can never be sure the provider is doing what was promised; and the child as the immediate consumer cannot be in a position to judge the quality of service. Regular testing has been promoted as a check on quality. But teachers can teach to the test. And worse, as we know from cheating scandals in Atlanta and many other cities, teachers can change wrong answers to right answers on bubble sheets once students are done.”

From the International Education News blog at Teacher’s College, Columbia.

The trouble with the argument is that it rests on the empirical question of whether student test-based accountability systems for schools can work, and though the question is not conclusively settled, my reading is that the evidence seems to be leaning in the direction of roughly “yes".

26 February 2025

What’s the single biggest growth opportunity that no-one really tried?

At present, around 1% of Ugandans live and work overseas (roughly 400,000 of a population of 37.6 million). This 1% of the population send home 4% of Uganda’s GDP in remittances. According to a Gallup poll, around 35% of Ugandans would permanently move to another country if they were allowed to. If they all could, and sent back as much as current Ugandans abroad do, that would be a one-off 140% increase in Uganda’s economy. Or if Uganda had the same level of emigration as the UK does (8%, 5.2 million of a population of 64.1 million Brits live and work overseas), that would be a 28% increase in Uganda’s economy. And that’s totally ignoring the increase in income for the actual migrants themselves. Median income in Uganda is $2.5 per day (in PPP), so even a job on UK (“relative-") poverty pay levels of around $23 per day would be a NINE-FOLD increase for them. Needless to say, the main reason that more Ugandans don’t work in high-wage economies, is that the governments of high-wage countries impose restrictions on the entry of people, particularly those from poorer countries.

Brain drain I hear you say? Michael Clemens killed that one too (ethically it is pretty unreasonable to restrict individual's freedom to such an extreme extent, even if there were any real evidence that emigration of highly-skilled people hurt an economy, which there isn't anyway).

So yes, clearly planning Kampala’s urban development is important for growth. But does it really have more “potential” than something that could double the country’s economy overnight?

12 November 2024

Is “technical assistance” counterproductive?

Duncan Green reviews a fascinating new AidData survey on what developing country policymakers think about donors.

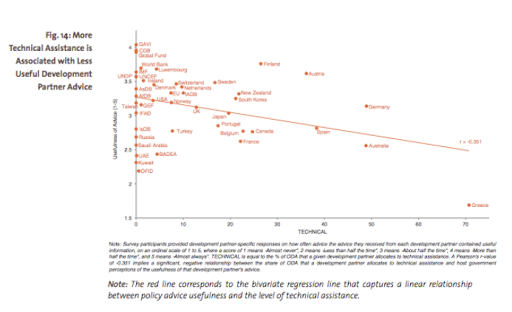

One of the key findings he points to is that

"Reliance upon technical assistance undermines a development partner’s ability to shape and implement host government reform efforts. The share of official development assistance (ODA) allocated to technical assistance is negatively correlated with all three indicators of development partner performance."

Obviously alarm-bells should be ringing about such firm causal conclusions being drawn from a correlation. One of the best ways of assessing these things is with some rigorous eyeball econometrics - take a look at this chart showing the relationship driving that claim.

Looks to me like that is a pretty weak relationship, and you could just as easily have drawn a totally flat line (no relationship). And indeed, deep in the weeds, Table E.11 tell us that this is a simple correlation between these two variables with a sample size of just 44 data points (countries). It might technically pass a statistical significance test, but it doesn’t really tell us that there is a reliable correlation, let alone causality. And even if you believed the estimated negative relationship - it’s really not huge - implicitly going from 0% aid on technical assistance to a massive 50% of aid spent on technical assistance would only reduce the perceived quality of your advice by 0.55 points on a 5 point scale.

Bottom line for technical assisters - don’t give up your day job quite yet.

02 November 2024

Why are people so opposed to immigration? #142538

As the evidence piles up that migrants don’t steal jobs (one of the implications of them being human beings is that migrants also buy stuff - so they create exactly as many new jobs as they “take”), some of the more sophisticated immigration opponents turn to the negative impacts of immigration on other things such as housing or public services instead to support their case.

So what does the research evidence say about the impacts of immigration on public services? Really very little actually. The University of Oxford’s Migration Observatory says that there is “no systematic data or analysis.” In health, we know that many healthcare providers are immigrants, but it’s hard to know the impact of migrants as users of health services as (rightly) nobody records people’s migration status when they go to the doctor.

Using household survey data, Jonathan Wadsworth at Royal Holloway found that (shock!) immigrants tend to use GP services and hospitals at roughly the same rate as natives (via Ferdinando Giugliano in the FT).

Taking another approach, a new paper by Osea Giuntella from the Blavatnik School of Government at Oxford, combines household survey data with administrative data on NHS waiting times. Do you need to wait longer for a referral or in A&E in places where there are more immigrants? Come find out at the CGD Europe research seminar on Weds 18 Nov (there will be sandwiches).

23 July 2025

New education economics papers

A few papers caught my eye from last month's repec new education economics papers feed. All from developed countries, but such is economics, a lot of the interesting new research happens on rich countries where the researchers are more likely to know about interesting policies and institutional features to study, and where there is better data (both problems which RISE is seeking to address, by encouraging collaborations between developing country-based researchers and leading academics based at top universities in rich countries, and also by funding new data collection in developing countries).

"Quantifying the Supply Response of Private Schools to Public Policies” by Michael Dinerstein and Troy Smith looks at a reform in New York which increased the budget for some public schools, finding an increase in enrolment at these schools, and that nearby private schools lost business and were slightly more likely to shut down. In an interesting twist, whilst the reform improved quality at the public schools that received extra money, the movement of some students from higher quality private schools to lower quality public schools meant that overall outcomes from the school system were not improved. All of which reminds me of the recent story from Rwanda that some private schools seem to be going out of business by the growth of public schools. What is that shift doing to the overall quality mix?

“The Information Value of Central School Exams” by Guido Schwerdt & Ludger Woessmann compares students in Germany who graduated from states which use a centralized common school-leaving exam to those with a local school-set leaving exam. Better grades are roughly three times more valuable in the labour market when they come from centralized exams than from school-set exams. In Lagos, private school associations are currently in the process of joining together to put their students through common school leaving exams for partly this reason.

Nicola Bianchi’s Job Market Paper looks at "The General Equilibrium Effects of Educational Expansion” - when Italy expanded STEM higher education in 1961, enrolment increased by 200%. However - those students who enrolled didn’t earn any more than they would have had they not enrolled, because the massive increase in the supply of qualified students reduced the labour market premium for that qualification, as well as the quality of education suffering due to congestion and peer effects. Which of course should remind you of Lant’s classic “Where has all the education gone?"

How much does the new deworming replication matter for Effective Altruists?

It doesn’t at all, as far as I can tell. As Calum points out, what matters is the systematic review of evidence not one study. And the new Cochrane systematic review doesn’t seem to have responded to the criticism from Duflo et al to their 2012 review, that it ignores quasi-experimental and long-term evidence on positive impacts of deworming (specifically Bleakley 2004, Ozier, and Baird et al).

A replication of the famous Miguel and Kremer deworming paper that launched the whole RCT in development economics movement, is published in the Journal of International Epidemiology today (along with comment from Hicks, Kremer, and Miguel, and reply from the replication authors), with coverage in the Guardian and by Ben Goldacre for Buzzfeed.

You may remember Berk Ozler's review of the draft of the replication paper back in January - concluding

"Bottom line: Based on what I have seen in the reanalysis study by DAHH and the response by HKM, my view of the original study is more or less unchanged."

You can probably expect to see more on the replication coming from @cblatts, which I’m not going to get into, but back in 2012, Givewell were convinced that the Cochrane review shoudn’t change their recommendation to donate to the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative or Deworm the World.

The ambiguity does make me a little queasy, and pushes me more in the direction of GiveDirectly (I see basically zero risk that giving $1000 to someone on a very low income can really be totally wasted, in the way that an ineffective drug could theoretically have zero impact).

16 June 2025

Global Organ Trade

Here’s a great idea from Al Roth, the 2012 Economics Nobel Prize winner.

Al got his prize for developing his theoretical matching ideas into a computerized kidney exchange - so if you want to donate a kidney to a family member but you aren’t the right match, you can find another pair of people in the same situation from a different city and criss-cross the pairing, so both kidney transplants can go ahead.

In his new book (reviewed here by Alex Tabarrok), Al proposes extending the kidney exchange internationally.

"Mr. Roth, however, wants to go further. The larger the database, the more lifesaving exchanges can be found. So why not open U.S. transplants to the world? Imagine that A and A´ are Nigerian while B and B´ are American. Nigeria has virtually no transplant surgery or dialysis available, so in Nigeria patient A’ will die for certain. But if we offered a free transplant to him, and received a kidney for an American patient in return, two lives would be saved.

The plan sounds noble but expensive. Yet remember, Mr. Roth says, “removing an American patient from dialysis saves Medicare a quarter of a million dollars. That’s more than enough to finance two kidney transplants.” So offering a free transplant to the Nigerian patient can save money and lives. It’s hard to think of a better example of gains from trade (or a better PR coup for the U.S. on the world stage). Better matching with computerized markets is saving lives, but more than 100,000 people are still waiting for kidneys in the United States alone."