This post first appeared on the RISE blog

The recently launched report by the Education Commission has confirmed that a "business as usual" expansion of inputs is not going to fix the global learning crisis.

The recently launched report by the Education Commission, led by Commission Chair Gordon Brown, a star-studded cast of global leaders (including Center for Global Development affiliates Larry Summers and Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala), and guided by Commission Directors Justin Van Fleet and Liesbet Steer, has brought fresh data and support to the research agenda at RISE. There is a global learning crisis on a massive scale and a “business as usual” expansion of inputs isn’t going to fix it.

First, we’re very happy to see the high frequency of the word “learning”. Although educationists highlighted learning deficits of those in school (eg the 1990 Jomtien Declaration’s opening paragraphs stressed: “...millions more satisfy the attendance requirements but do not acquire essential knowledge and skills”), the UN Millennium Development Goals distorted the agenda onto an exclusive focus on enrolment and primary completion. Learning is, of course, harder than enrolment to reduce to the thin measures that are easy for states to “see,” but that is a weak excuse.

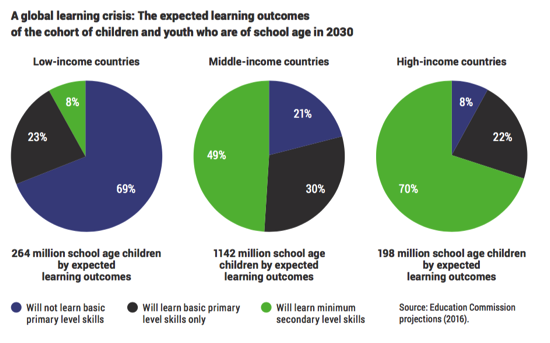

We knew already that the majority of children who can’t read are now *in* school (eg Spaull and Taylor for Southern Africa, the Global Monitoring Report), but the Commission report draws out the implications of current trends for 2030. Their calculations suggest that if current trends continue, 69% of school-aged children in low income countries will not have learnt basic primary level skills by 2030 - despite high enrolment rates. Even in middle income countries, half of children will attain primary level skills only. Millions of children are going to sit through hours of school day after day, and still not acquire the skills they need to prepare them for the complex and rapidly changing world they will face.

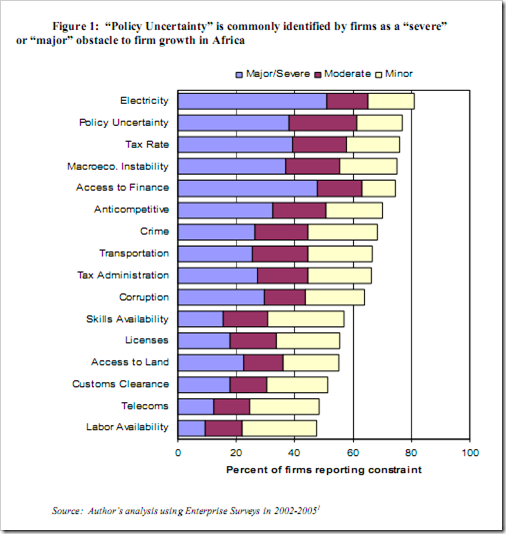

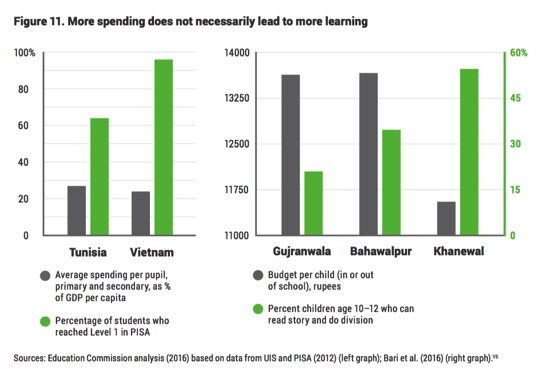

Second, what can we do about the global learning crisis? The Commission report leads with a discussion of the need for reform to systems which are coherent around learning performance. They provide new evidence that simply spending more money alone cannot be the answer. For example, Vietnam spends less money on education than Tunisia, yet scores much better in terms of learning outcomes (one of the reasons RISE picked Vietnam as a focus country). The same pattern is observed across cities in Pakistan, where Khanewal spends a fraction of other cities and yet achieves better results.

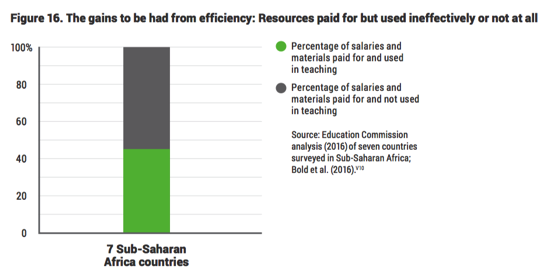

Even more shocking are the results from Africa. The Commission digs into an important new paper by Tessa Bold and co-authors (the draft presented at the RISE Conference) looking at the World Bank’s Service Delivery Indicators survey in seven countries. Analysis by the Commission reveals that less than half of spending on salaries and materials is actually used in teaching.

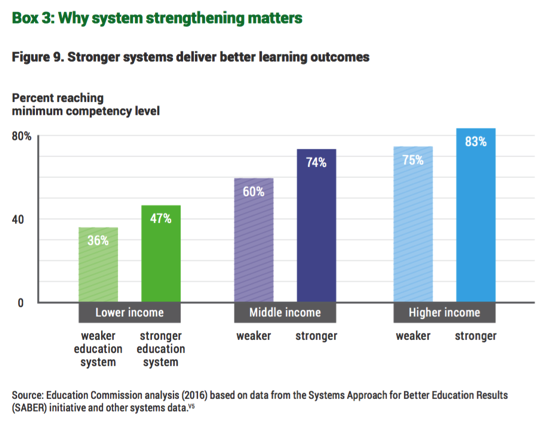

It is clearly possible to use existing resources more efficiently, and do more with less. RISE aims to understand the efficiency of schools in creating learning through a systems based approach. The best measure that is currently available for measuring features of systems, such as policies on teachers or student assessments, is the World Bank Systems Approach for Better Education Results (SABER) initiative. Each of our RISE Country Research Teams will carry out a baseline assessment of the system they are studying, based on SABER instruments. Analysis by the Commission report highlights the importance of systems in explaining performance - countries with stronger system features, as measured by the SABER surveys, score better on learning assessments.

The Education Commission report strengthens the case for research into how to reach high performing education systems to accelerate learning progress. It would be a tragedy if their “business as usual” projection becomes the sad reality, and when the end of the UN Sustainable Development Goals is reached in 2030, the majority of children emerge from school unprepared for the challenges they will face.

For more analysis listen to CGD Senior Fellows Bill Savedoff and Justin Sandefur discuss the report on the CGD podcast with Rajesh Mirchandani.