I was a bit disappointed by Julia Unwin's new short book "

Why Fight Poverty?". The subtitle on the US amazon edition is perhaps a better title: "And Why it is So Hard". The most interesting part of the book is about the emotional responses to poverty that make it it hard to get the public to care - shame, fear, disgust, difference, mistrust. She doesn't address why it is so hard to get the public to care about global poverty.

I knew the book would be about UK poverty (Julia Unwin is Chief Exec of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, which has been working on UK poverty since 1904), but maybe I hoped for a more substantial treatment of the difference between UK and international poverty. Actually to be honest I was probably just annoyed that she dismisses those (like me) who claim that we should think differently about rich world poverty and extreme poverty in poorer countries. This is the sum total of discussion about international poverty in the book:

"[many] argue that while there is real poverty in other countries, any poverty in the UK is less severe, and describing it as such is misleading and untruthful. They are right to some extent ... [but] All poverty is relative and needs to be seen in context. Needs are relative in every society and differ depending on the price of food and other goods, and social norms ... Because UK poverty is relative, it can be easier to ignore or dismiss - but it is real and affects a sizeable portion of our population."

I've written before about why I'm sceptical about the relative importance of relative poverty, but I also worry about too quickly dismissing the experiences of people living in the UK.

Jack Monroe has given powerful descriptions of her own experience living with poverty and hunger in the UK.

"Poverty isn’t just having no heating, or not quite enough food, or unplugging your fridge and turning your hot water off ... Poverty is the sinking feeling when your small boy finishes his one weetabix and says ‘more mummy, bread and jam please mummy’ as you’re wondering whether to take the TV or the guitar to the pawn shop first, and how to tell him that there is no bread or jam."

"sitting across the table from your young son enviously staring down his breakfast ... it’s distressing. Depressing. Destabilising. ... Imagine those 77 days of being chased for rent that you can’t pay, ignoring the phone, ignoring the door, drawing the curtains so the bailiffs can’t see that you’re home, cradling your son to your chest and sobbing that this is where it’s all ended up. It feels endless. Hopeless. Cold. Wet."

You should read both in full. It breaks your heart. And yet... thanks to her blog,

Oxfam invited Jack to Tanzania, to meet some of the people they work with. Jack concluded;

"Our experiences of hunger and poverty are different, but we need to see the similarities too."

Well yes. But let's think about those differences and similarities, and make that comparison.

Going hungry is much more common in Tanzania than it is in the UK. Maybe that makes it relatively less bad, psychologically less painful? I imagine it might. You might be less likely to imagine hunger as a personal failure in a society where it is more common. And yet... Perhaps it's time to put some numbers on this.

Let's say that the single mother who Jack met in Tanzania - Irene - earns £200 per year. This is below the poverty line, and 15% less than the average (median) income of around £230 a year.

Let's say that someone like Jack living in poverty in the UK earns £10,000 a year. Below the poverty line, and less than half of average income of £21,000 (these numbers aren't exact, but they are realistic).

So if we agree that "poverty is relative and needs to be seen in context", that "needs are relative", well for her relative income, Jack (48% of average income) is much worse off than Irene (87% of average income). But is Jack really worse off than Irene? The same? Similar? Comparable? Remembering that in absolute terms she earns 50 times more than Irene?

What if we flipped it around. Imagine a very rich society. Perhaps it is Britain in 100 years, after 3% annual growth. Average income is now £400,000. A single mother - Abby - living in poverty, earns "just" £100,000. That is a quarter of average income. Relatively speaking, Abby is now much worse off than Jack. Do you feel sympathy for Abby, on her relative pittance of £100,000? Or does that sound silly? And yet Jack is more similar to Abby (Jack earns 10% of Abby's income) than Irene is to Jack (Irene earns just 2% of Jack's income).

Or to take another example, think about this headline from

the Atlantic: "

America’s 1% live in relative poverty compared to the .01%". The top 1% in America earn a measly $2 million a year, just a fraction of the $30 million that the top .01% earns. If the top 1% all decided to set up their own new country, Richland, should we suddenly start feeling sympathy for the lowly $2 million a year earners, who are on just a small fraction of the median income, and well below the relative poverty line?

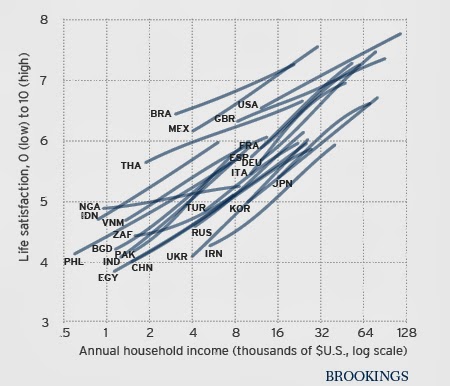

The other thing to consider when what we're really interested in is some concept of wellbeing rather just cash, is what happens when we try and directly measure wellbeing? Gallup surveys have asked individuals around the world to rate their own life satisfaction on a scale of 1 to 10. If relative poverty in the UK was comparable to poverty in developing countries in terms of their lived experience rather than in terms of their income, we might expect to see some similarity in self-reports of life satisfaction.

Well, the difference in life satisfaction is perhaps unsurprisingly much smaller than the income gap (life satisfaction is measured on a bounded 1-10 scale, but income is measured on a much wider and unbounded scale). But the surveys show that even the poorest people living in developed countries like the UK report higher levels of life satisfaction than everyone in developing countries, almost no matter what they earn. You can just about make out from the chart below; the poorest in Britain (GBR) are more satisfied with their life than the richest in Indonesia (IDN), Nigeria (NGA), India (IND), Pakistan (PAK), and South Africa (ZAF) (for more details see the Brookings briefing, based on a paper by Stevenson and Wolfers).

So. In conclusion, I suppose I remain sceptical about relative poverty.