Teacher absenteeism is a huge problem in developing countries, wasting

up to a quarter of all spending on primary education in developing countries.

The 2014

Education for All Global Monitoring Report, which was launched in London last week, puts the problem mainly down to the low pay and poor working conditions of teachers.

"While teacher absenteeism and engagement in private tuition are real problems, policy-makers often ignore underlying reasons such as low pay and a lack of career opportunities. ... Policy-makers need to understand why teachers miss school. In some countries, teachers are absent because their pay is extremely low, in others because working conditions are poor. In Malawi, where teachers’ pay is low and payment often erratic, 1 in 10 teachers stated that they were frequently absent from school in connection with financial concerns, such as travelling to collect salaries or dealing with loan payments. High rates of HIV/AIDS can take their toll on teacher attendance."

The report includes this chart, showing that in a handful of countries teachers earn below $10 a day (which they have decided is not enough to live on).

Which seems jarring when the same week there was a

conference on the economics of education in developing countries, where much of the literature is focused exactly on this issue of teacher absenteeism, and finds very little evidence that low pay is the main factor (as opposed to, say, weak or non-existent systems of accountability). In India it is well documented that whereas absenteeism is roughly similar in public and private schools, teachers in public schools are paid more than 5 times as much as private school teachers.

(See for example this chart from data from

Singh 2013, or similar from

Kremer et al 2005,

Alcazar et al 2006 in Peru, or

African data here)

Harry Patrinos of the World Bank

writes:

"There is very little evidence that higher salaries lead to better attendance, however. Contract teachers have the same or higher absence rates. Compared to public school teachers, though, private school teachers are absent less, even though contract and private school teachers alike take home much less pay than their regular civil service public school teacher counterparts."

As little as teachers might make in some countries, they are still doing well relative to most other people. In many countries public primary school teachers are the 1%.

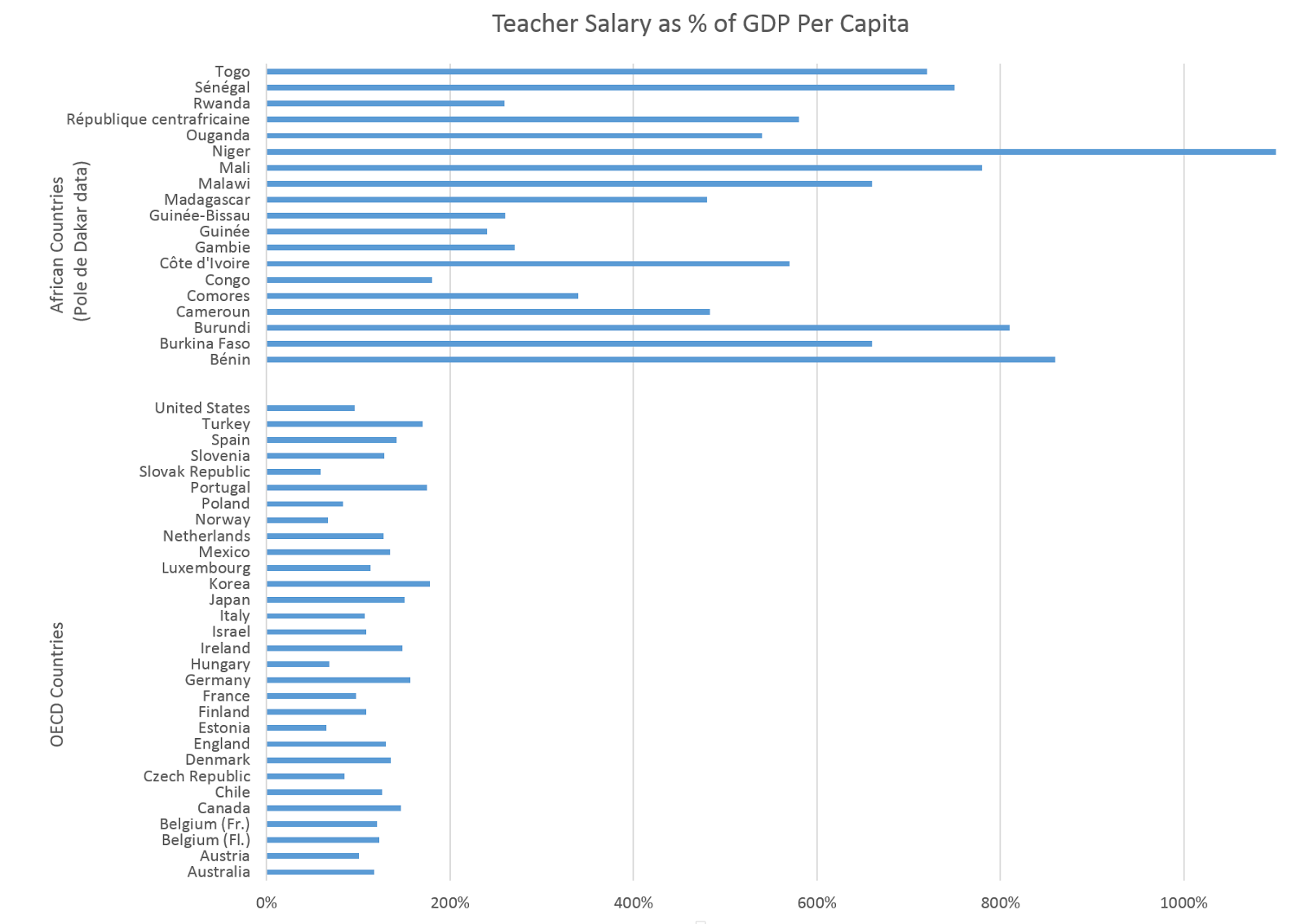

I thought I'd take a quick look at the data presented in the GMR and see what those teacher salaries are presented as a % of GDP. In OECD countries, average teacher salary is roughly around the same level as GDP per capita. In African countries, the average teacher salary is 3 - 4 times GDP per capita.

Karthik Muralidharan summarised the state of public schools in India as facing two problems; governance and pedagogy. This probably generalises to much of the developing world. What this GMR comes across as doing is focusing almost entirely on the pedagogy problem, and sweeping the governance problem under the carpet (receiving roughly 10 pages attention out of a 300 page report). Perhaps this is a welcome counterbalance to prominent World Bank research which focuses much more on the governance problem. But really shouldn't a major flagship state of the sector report aspire to properly tackle both? Of course fixing the pedagogy problem means working with teachers to improve their capabilities and not demonising them or calling them all lazy slackers. But neither can we just ignore the reality of skiving on a massive scale (or: Don't hate the player, hate the game).