This post first appeared on the CGD blog Views from the Center

Accountability in school systems is essential to deliver better learning and accelerate progress in developing countries. What is still really lacking—and what RISE is working towards (such as with Lant Pritchett’s coherence paper)—is a coherent and complete analytical framework capturing the key elements of a system of school accountability that can explain the divergent experiences we have seen in school reform.

The latest issue of the

Journal of Economic Perspectives has a great symposium on schools and accountability, covering much of the research that motivated the development of RISE. Here are a few of the research highlights:

- Isaac Mbiti (part of the RISE Tanzania team) discusses “The Need for Accountability in Education in Developing Countries.”

- Brian Jacob & Jesse Rothstein dig into how we measure student ability in modern assessment systems (including some helpful discussion of what IRT can and can’t do).

- David Deming & David Figlio draw lessons from US experience with test-based school accountability systems, including caution about unintended consequences and ‘gaming,’ and noting that accountability seems to work best for low-performers.

- Julia Chabrier, Sarah Cohodes, and Philip Oreopoulos sum up what we can learn from charter school lotteries, re-emphasizing the point that charter schools seem to work best in neighbourhoods with poor performing schools.

Here though I’m going to focus on Ludger Woessmann’s article, "The Importance of School Systems” to help break down the possible reasons for the differences in performance across systems.

1. Why school systems matter: Your country matters for your test score

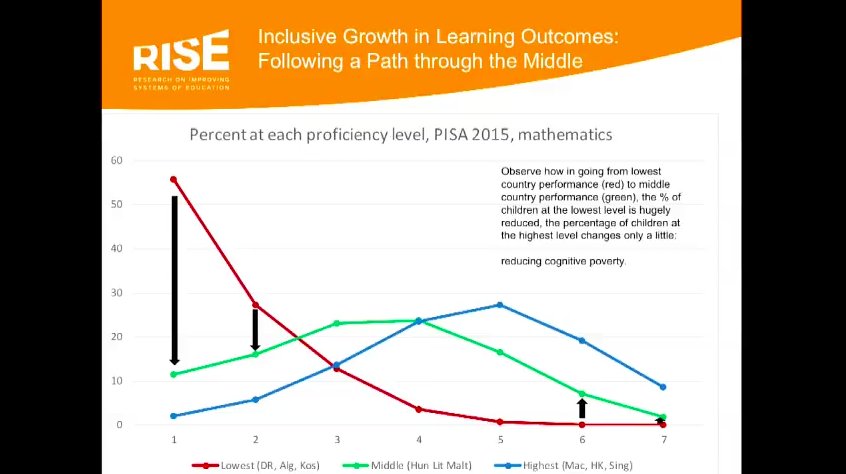

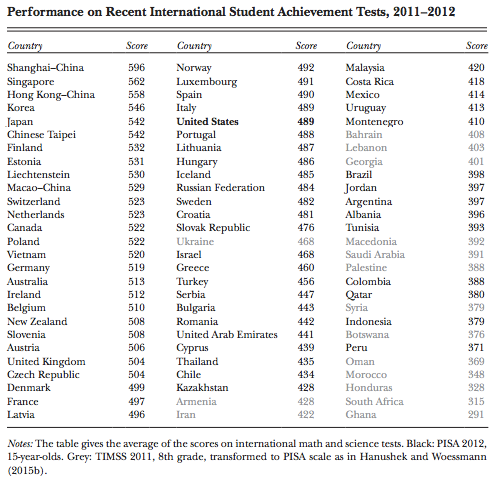

Woessmann starts by documenting the size of the gap in learning performance of 15-year-olds across countries, using combined PISA and TIMMS scores. As a rule of thumb, children learn on average between 25-30 points per year on this scale, which means that the average 15-year-old in the best performing countries (Singapore & Hong Kong) is roughly two years ahead of the average OECD country (for comparison, the UK scores roughly around this OECD mean).

Down at the other end, the average 15-year-old in Peru or Indonesia is well over 100 points below average—at least four years behind the UK. Ghana and South Africa are more like 200 points below average—6-7 years behind the UK/OECD average. This means that if a typical UK 15-year-old is in year (grade) 10, then the average Ghanaian 15-year old is just at grade 3 level.

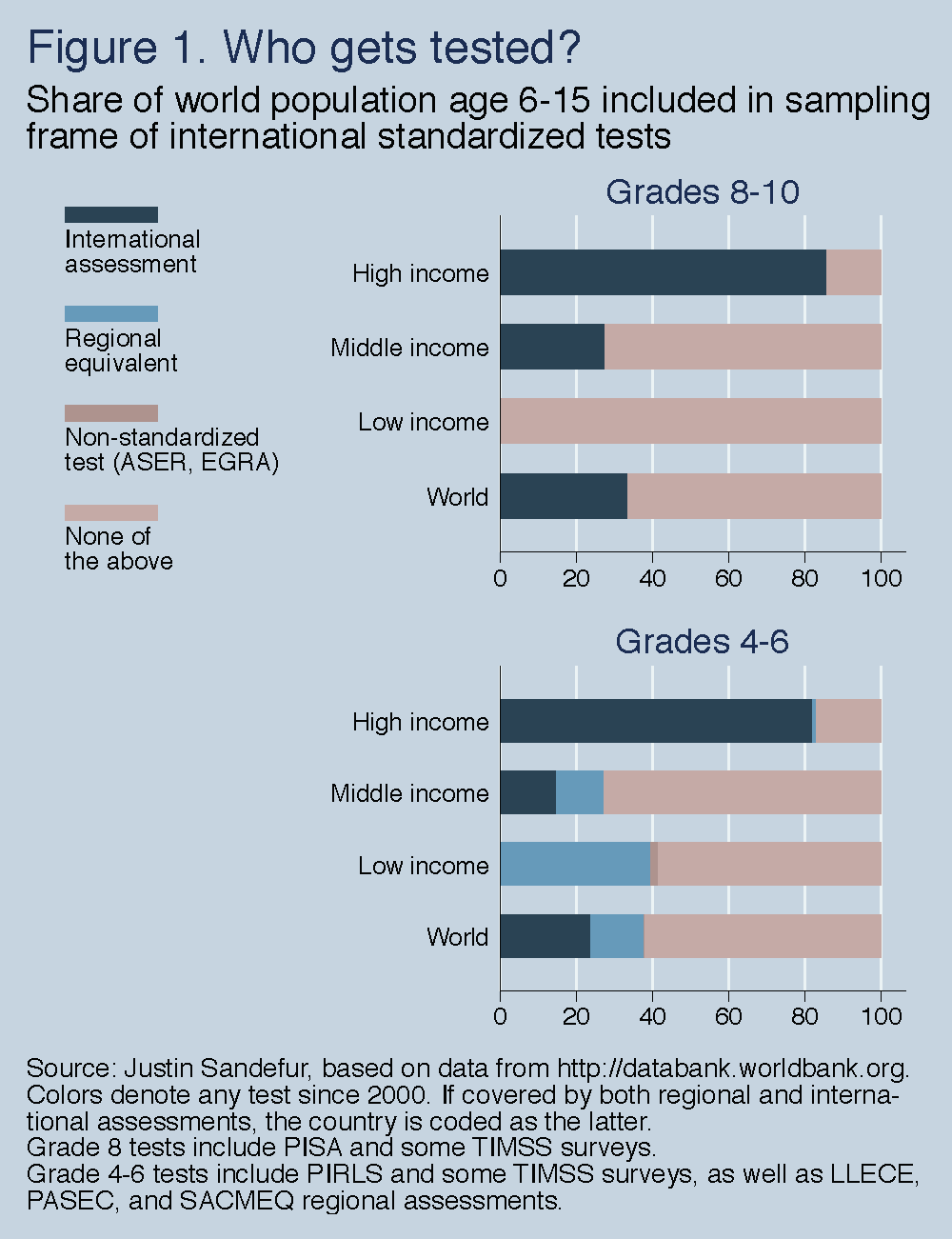

Whilst the data for the poor countries we do have is really

really bad, for most poor countries we don’t even have any data. In his blog post, “The Case for Global Standardized Testing,” Justin Sandefur highlights just what a tiny percentage of the population of low-income countries are covered by any internationally comparable standardized assessment. It’s essentially indistinguishable from the zero percent of students included in international assessments. Even the regional assessments (which provide some comparability) only cover 40 percent of kids from low-income countries, and only at primary school level. By contrast, 80 percent of children from high-income countries are covered at both primary and secondary level in international tests.

2. Country or school factors?

Is the difference in test scores among countries really about school quality though, or rather is it just national wealth, culture, or something else? Woessmann presents a mammoth international “education production function” exercise looking at correlates of test scores across over 200,000 students in 29 countries.

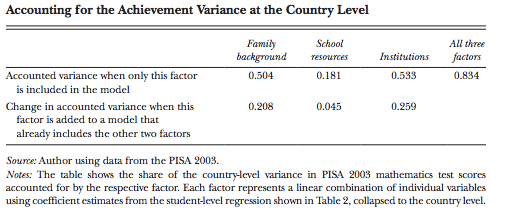

He finds that specific features of systems (such as school autonomy or centralised leaving exams) do correlate with student performance. Further, together these school system variables seem to matter more than student’s family background or school resources.

Moreover, features of the education system seem to matter 3-5 times more as additional variables in explaining outcomes than the level of school spending (adding 0.259 vs. 0.045 in explanatory power).

He also cites Abhijeet Singh’s research (part of the RISE India team), who demonstrates that gaps between students across countries are small when they enter school, and grows as they progress through the school system.

3. Correlation or causation?

The “education production function” approach that Woessmann takes here is explicitly based on correlations as it is difficult to impossible to nail causality down at the aggregate level.

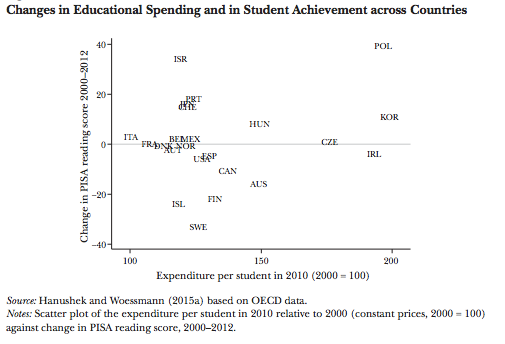

But one first step is to look at

changes in variables rather than levels. Take spending: whereas you might be able to find a positive correlation between GDP or the level of education spending and student learning, when you look at increases in spending, there is no correlation with increases in learning—which suggests that just looking at levels rather than changes is confounded by something else (e.g., while richer countries might spend more and have better test scores, it’s not the spending that causes the test scores, but insteada third factor correlated with both).

4. Money aside, what about other “inputs”?

Spending aside, Woessmann goes on to review what the rest of the literature says about three key inputs (for a look at other inputs, see the RISE working paper by Paul Glewwe & Karthik Muralidharan).

- Class Size: has “a limited role at best"—for example, a 2002 paper by Woessmann used quasi-random variation in small sizes to demonstrate the generally small and heterogeneous effect of class size in different countries.

- Instruction Time: is better, and "can increase educational opportunities.”

- Teacher Quality: (as measured by gains in student performance) "is related to better student achievement." (It’s worth noting that none of the “thin input” measures of teacher quality (such as qualifications or experience or pay) have substantial effects on learning.)

5. So what features of *systems* leads to more of these inputs and better performance?

- External exams: "A large literature has shown consistent positive associations between external exams and student achievement” (including cross-country analysis but also a cross-subject diff-in-diff approach within Germany).

- School autonomy: "School autonomy has a significant effect on student achievement, but this effect varies systematically … part of the negative effect of school autonomy stems from a lack of accountability” (including with a country fixed effects approach looking at changes over time).

- Private competition: "Cross-country evidence suggests a strong association of achievement levels with the share of privately operated schools” (robust to exogenous variation based on historical differences in religion).

- Tracking: "earlier tracking tends to raise the inequality of educational outcomes."

All of these points reiterate those made in various RISE-framing documents. School systems really matter—the differences in performance across systems are huge, and much of the gap seems to be attributable to real differences in school quality across systems, rather than other country-specific characteristics. And much of the discrepancy in school quality seems to be related to aspects of systems around accountability.

RISE is continuing to sort out and analyze these diverging experiences in school reform—and more importantly how developing countries can accelerate their progress towards global standards of learning.