A new NBER study exploits the NYC centralised school admissions database to understand how parents choose which schools to apply for, and finds (shock!) parents choose schools based on easily observable things (test scores) rather than very difficult to observe things (actual school quality as estimated (noisily!) by value-added).

Value-added models are great — they’re a much fairer way of judging schools than just looking at test scores. Whilst test scores conflate what the student’s home background does with what the school does, value-added models (attempt to) control for a student’s starting level (and therefore all the home inputs up that point), and just looking at the progress that students make whilst at a school.

David Leonhardt put in well;

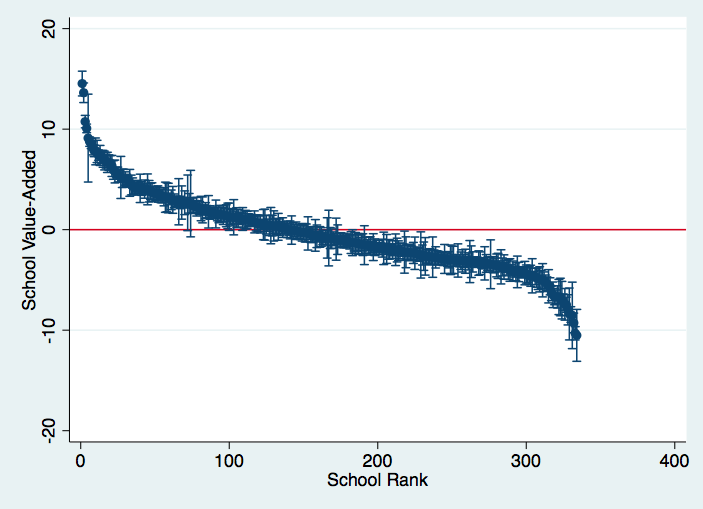

“For the most part, though, identifying a good school is hard for parents. Conventional wisdom usually defines a good school as one attended by high-achieving students, which is easy to measure. But that’s akin to concluding that all of LeBron James’s coaches have been geniuses.”Whilst value-added models are fairer on average, they’re typically pretty noisy for any individual school, with large and overlapping confidence intervals. Here’s the distribution of school value-added estimates for Uganda (below). There are some schools at the top and bottom that are clearly a lot better or worse than average (0), but there are also a lot of schools around the middle that are pretty hard to distinguish from each other, and that is using an econometric model to analyse hundreds of thousands of data points. A researcher or policymaker who can observe the test score of every student in the country can’t distinguish between the actual quality of many pairs of schools, and we expect parents to be able to do so on the basis of just a handful of datapoints and some kind of econometric model in their head??

Making school quality visible

If parents don’t value school effectiveness when it is invisible, what happens if we make it visible by publishing data on value-added? There are now several studies looking at the effect of providing information to parents on test score levels, finding that parents do indeed change their behaviour, but there are far fewer studies directly comparing the provision of value-added information with test score levels.

One study from LA did do this, looking at the effect of releasing value-added data compared to just test score levels on local house prices, finding no additional effect of providing the value-added data. But this might just be because not enough of the right people accessed the online database (indeed, another study from North Carolina found that providing parents with a 1-page sheet with information that had already been online for ages already still caused a change in school choice).

It is still possible that publishing and properly targeting information on school effectiveness might change parent behaviour.

Ultimately though, we’re going to keep working on generating value-added data with our partners because even if parents don’t end up valuing the value-added data, there are two other important actors who perhaps might — the government when it is considering how to manage school performance, and the school themselves.