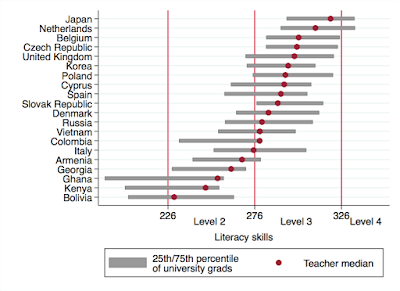

Eric Hanushek, Marc Piopiunik, and Simon Wiederhold published some fascinating analysis in a 2014 NBER working paper (link) comparing the literacy and numeracy of teachers to the overall population (with a university degree) in a range of OECD countries. In the figures below, the grey bars show the gap between the 25th and 75th percentile of skill for all university-educated adults in each country, and the red marker in the middle shows the median skill level of teachers in that country. Perhaps unsurprisingly, teachers in Finland are the highest skilled internationally, but also within Finland they are drawn from relatively high in the distribution of adults. This fits with common narratives about teaching being a particularly well-regarded, and selective, profession in Finland.

The second point to note from the figure is the remarkable regularity of average (median) teacher performance in each national distribution. There is some variation, but most teachers in high-income countries are roughly in the middle of the distribution of university educated adults. Teaching in lower-income countries tends to be more selective - the median teacher is much closer to the 75th percentile of adults in Colombia, Ghana, and Kenya.

These two facts, the low overall level of literacy skill amongst graduates in the lower middle income countries, and the position of teachers within the distribution, imply an upper bound on the ability of a more selective recruitment process to improve the average quality of teachers. If for example Ghana and Kenya managed to increase the selectivity of the teaching profession enough to raise average teacher skills to above the 75th percentile (something no other country has done), this level could still be well below Level 3 on the PIAAC scale.

Getting better teaching is critical for improving education in developing countries. This data highlights the scale of one aspect of the challenge. Education systems are going to have to figure out how to deliver for children with teachers who may be able to make "low-level inferences" but are unable to "navigate complex texts."

---

*Thanks to Laura Moscoviz at the Education Partnerships Group for assistance with the graph!

---

As far as I'm aware, no such comparison exists for low- and lower-middle-income countries. Tessa Bold and coauthors present results on the tragically low absolute level of teachers in sub-Saharan Africa (link), and similarly Justin Sandefur presents data comparing the skill level of teachers in sub-Saharan Africa to students in OECD countries (link). But neither compare the level of skill of teachers in Africa to teachers in high-income countries, and to the skill of other adults in Africa.

So I made one*. The World Bank's STEP Skills surveys use the same literacy assessment as the OECD PIAAC survey that Hanushek et al used, so I replicated and extended their graph, adding on the countries from the STEP data in which it was possible to identify teachers and their literacy level - specifically Vietnam, Colombia, Armenia, Georgia, Ghana, Kenya, and Bolivia.

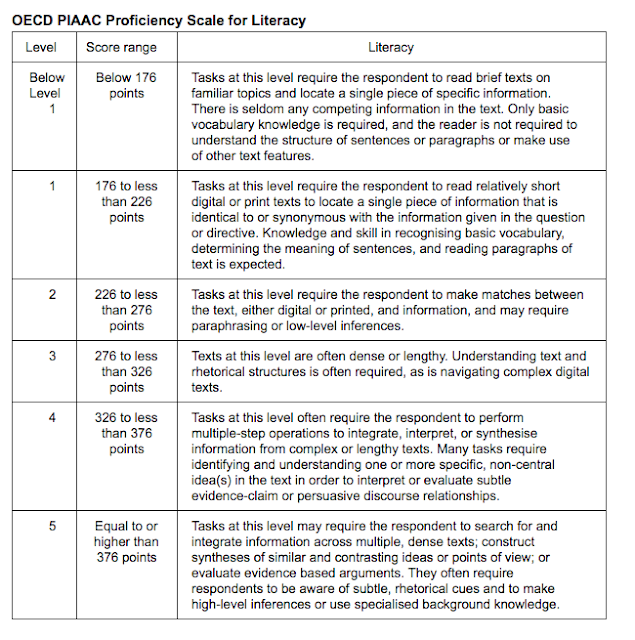

The first point to note is how low the overall distribution in lower income countries is. The majority of adults (in urban areas) who have graduated from university fall into the Level 2 category, whereas in high income countries most fall into Level 3. The PIAAC guide (copied below) explains what these levels mean: Level 2 tasks “may require low-level inferences” whereas Level 3 tasks require “navigating complex texts”.

These two facts, the low overall level of literacy skill amongst graduates in the lower middle income countries, and the position of teachers within the distribution, imply an upper bound on the ability of a more selective recruitment process to improve the average quality of teachers. If for example Ghana and Kenya managed to increase the selectivity of the teaching profession enough to raise average teacher skills to above the 75th percentile (something no other country has done), this level could still be well below Level 3 on the PIAAC scale.

Getting better teaching is critical for improving education in developing countries. This data highlights the scale of one aspect of the challenge. Education systems are going to have to figure out how to deliver for children with teachers who may be able to make "low-level inferences" but are unable to "navigate complex texts."

---

*Thanks to Laura Moscoviz at the Education Partnerships Group for assistance with the graph!

---